Caroline Guzi Savegnago, Ph.D. Student

Sha Tao, Ph.D., Associate Professor, stao@uga.edu/706-542-0658 Department of Animal and Dairy Science, UGA

Heat stress continues to be a challenge for the dairy industry, causing major economic losses. High temperatures and relative humidity commonly seen in the Southeast create a challenging environment that negatively impacts calf performance and welfare. Calves begin to experience heat stress even before birth. When dry cows are exposed to heat stress, their calves are often born lighter and less efficient at absorbing immunoglobulins from colostrum, which increases the risk of the failure of passive transfer. After birth, calves exposed to heat stress have higher respiration rates and body temperatures, reduced feed intake, impaired growth, and greater susceptibility to disease during pre- and postweaning periods. Despite these challenges, heat abatement strategies for calves remain less developed compared with those for lactating cows.

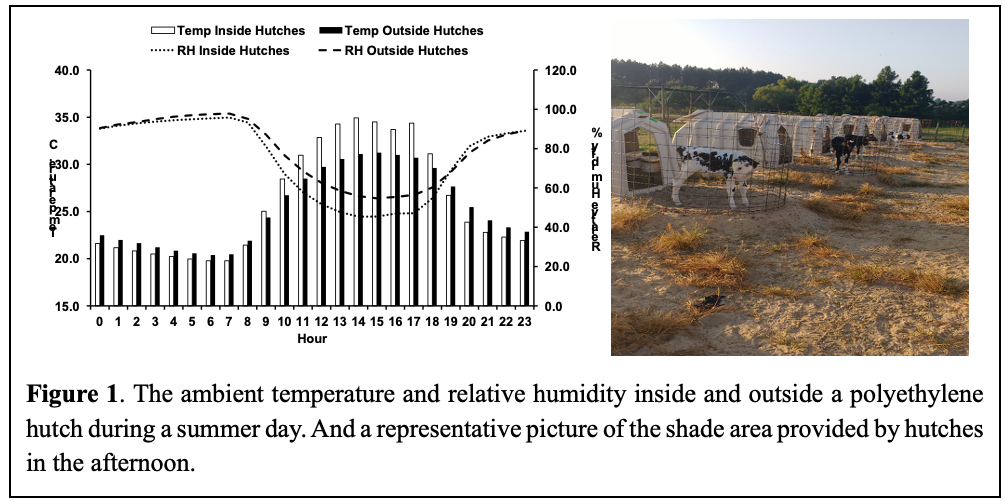

In the U.S., 38% of preweaned calves are housed in individual outdoor hutches (USDA, 2021). While individual hutches have the benefit of disease control, they are usually located in open areas that expose calves to extreme ambient temperature. Practical management, such as shade and forced ventilation can help reduce heat load on calves. Shade is a simple and effective method to cool calves. Providing shade to preweaned dairy calves decreases air temperatures in hutches and shows some benefits in calf health and welfare. If no shade can be provided, hutches can be oriented to face east to provide a small shade area in the afternoon. During summer, the ambient temperature inside a polyethylene hutch is 1.5-3.8 ○C higher than outside in the afternoon (Figure 1). Thus, a small shade from hutches in the afternoon can provide an area for the calf to escape high temperature inside the hutch without solar heating.

In addition to shade, forced ventilation using fans is well-established method for helping cattle dissipate heat. A study conducted in Ohio summer suggested that cooling using fans can increase calf body growth and feed efficiency prior to weaning. However, conflict results also exist. Depending on farm infrastructure, installing fans can be challenging for calves in individual outdoor hutches. During a continental summer, solar powered fan systems installed for outdoor calf hutches can achieve air speeds of 1.7 m/second inside the hutches. This reduces the internal hutch temperature and lowers respiratory rates and body temperature of calves; however, no improvements in intake or growth performance are observed. During subtropical summers, studies with individual or group-housed calves suggested that providing air speeds of 1.2 or 2 m/s at the calf level with fans improved thermoregulatory responses of calves, but no improvement on growth performance. Overall, providing heat abatement can effectively reduce heat load in calves, but its impact on growth performance remains inconsistent.

Similar with lactating cows, calves tend to consume less starter grain when temperatures are high, but they rarely refuse milk or milk replacer even offered in larger amounts. Therefore, strategies such as increasing the volume of milk fed to preweaning calves will provide extra energy to support growth, helping calves meet the demands for heat dissipation. Furthermore, an enhanced plane of nutrition not only promotes weight gain but may also improve immune function. However, cautions should be made when feeding large amounts of milk to calves during summer. Previous research suggested that abomasal emptying rate was delayed when milk replacer feeding rate was increased during summer. In other words, the milk will stay in the abomasum longer, which is a risk factor for the development of abomasal bloating. With larger amount of milk or milk replacer offered to calves during summer, the feeding frequency may increase as well.

Heat stress also exacerbates dehydration as calves lose more water through respiration and sweating. Water intake rises with ambient temperature, and calves during summer may double the water intake. Offering clean, fresh water from the first week of life is essential for young calves. Extra attention should be given to calves less than two weeks old, as they are more vulnerable to diarrhea, which can quickly lead to dehydration. During summer, it is essential to provide electrolytes to scour calves to help them replace lost fluids and maintain hydration.

Warm weather promotes the growth of bacteria, algae, and mold, and fly numbers rise around calves. These can increase the risk of calf health problems such as scours, pneumonia, and pinkeye. Therefore, it is important to clean and sanitize buckets, bottles, nipples, and other feeding tools after each use and keep bedding clean and dry. To help with fly control one may consider including larvicide or other fly control additives in feed. Managing tall grass, spoiled feed, and manure near areas close to calf housing and lactating herd can be a good strategy to lessen the fly pressure.

Managing heat stress in young calves requires both environmental and nutritional strategies. Shade, ventilation, and access to clean water help calves handle heat stress, while enhanced milk or milk replacer feeding programs can provide extra energy to support growth and immune function. The combination of these approaches may improve calf health and performance during summer, supporting long-term productivity of the herd.