Articles in this month’s issue include:

- Nutrient Requirements in Cotton (Henry Sintim and Glen Harris)

- Planting Considerations Following a Much Needed Rain (Camp Hand)

- UGA Weather Network and Stand Establishment in East Georgia Cotton (Wade Parker)

- Early Season Staging of the Cotton Crop (John Snider, Camp Hand, Josh Lee)

- Weather and Climate Outlook (Pam Knox)

- Early Season Irrigation Requirements for Cotton Production (Wesley Porter, David Hall, Jason Mallard, Phillip Edwards, and Daniel Lyon)

- In-Field Planter Considerations (Simer Virk and Wes Porter)

- Early Season Nematode Update for 2023: Make Careful Decisions Before Closing the Furrow (Bob Kemerait)

- Supplemental Control of Thrips with Foliar Insecticides (Phillip Roberts)

- Thrips Management in ThryvOn Cotton (Phillip Roberts)

- Carefully Manage Benghal Dayflower aka Tropical Spiderwort or Watch It Spread! (Stanley Culpepper)

Nutrient Requirements in Cotton (Henry Sintim and Glen Harris): Adequate and balanced supply of nutrients is necessary to optimize the productivity of cotton, just as any other crop. Without the right balance and amount of nutrients, plant growth would be impaired, significantly reducing yield and quality, or even leading to crop failure under severe nutrient stress. Plants require primary nutrients in greater amounts, followed by secondary nutrients, and then micronutrients. The relative amounts of the essential nutrients required for plant growth are, however, not indicative of their relative importance. The relationship between micronutrient deficiency and yield is just as important as that between macronutrients and yield. The concept is best illustrated by ‘The Law of the Minimum’, which indicates that growth is dictated not by the total resources available, but by the scarcest resource (limiting factor). In other words, growth occurs at the rate permitted by the most limiting factor.

Soil testing is a valuable technique to know the nutrient levels in the soil and to determine nutrient recommendations. The University of Georgia Extension fertilizer recommendations for cotton are based on yield goals. Nutrient uptake by cotton varies substantially by yield, as depicted in Table 1, which compares the nutrient uptake of cotton at different yield levels. As can be seen, increasing the yield from 892 lbs/ac to 1,606 lbs/ac (80% yield increment) led to a corresponding increase in the uptake of all the nutrients that were assessed, with calcium being the only nutrient that did not increase at a greater level than the yield increase. A similar trend in the nutrient uptake dynamics was observed when the cotton yield increased from 892 lbs/ac to 2,141 lbs/ac.

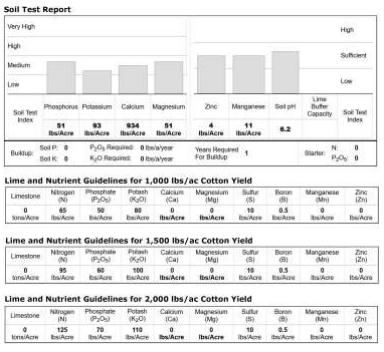

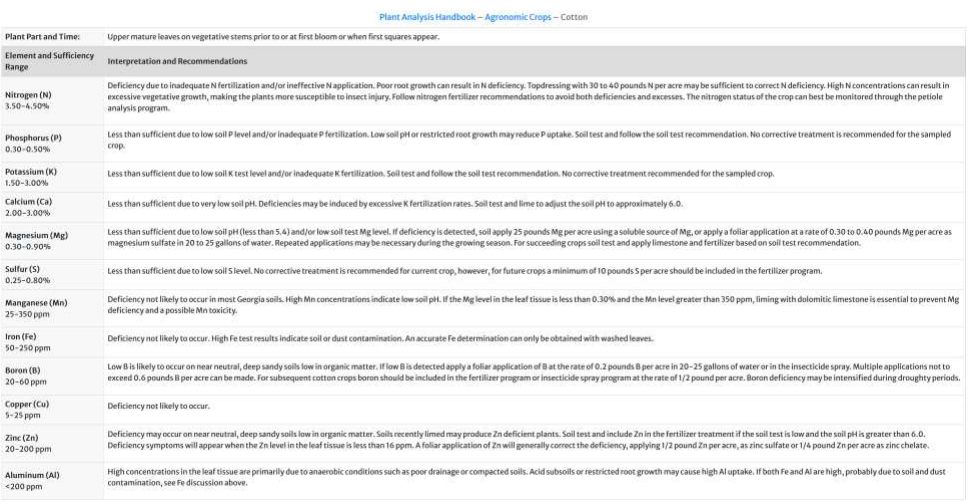

Nutrient recommendations for greater cotton yields in the state are by adjusting the nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium levels. Figure 1 shows the soil test report of a soil sample collected in Tifton, and the nutrient recommendations for different yield goals. These recommendations are based on maximizing the return on investment of fertilizer application, and not just by obtaining high yield. With several cotton fields in Georgia having a history of poultry litter application, it is expected that they will replenish the soils with micronutrients, which are required in smaller amounts. Also, several Georgia soils have kaolinite as the dominant clay mineral, and they are dominated by oxides of iron. Thus, iron is less likely to be limited under the low soil pH conditions prevalent in the state. It is important to note, however, that plant nutrient uptake is regulated by several abiotic and biotic factors. The availability of nutrients in the soil does not guarantee they will be taken up by the crop [4]. Thus, complementing soil test with in-season plant tissue analyses can be an effective way to monitor the nutritional health of crops, and to inform timely nutrient management [4–6]. Figure 2 shows the recommended nutrient sufficiency ranges for plant tissue analyses for cotton.

Table 1: Comparison of nutrient uptake in cotton at different yield levels (892 vs. 1,606 lbs/ac yield and 892 vs. 2,141 lbs/ac yield). Adapted from Rochester [3], which was based on a six year-study in Australia.

Figure 1: Soil test report and lime and nutrient guidelines for 1,000; 1,500; 2,000 lbs/ac cotton lint yield following UGFERTEX, a University of Georgia Extension Windows-based online system for formulating prescription lime and nutrient guidelines for agronomic crops (https://aesl.ces.uga.edu/calculators/ugfertex/).

Figure 2: The University of Georgia Extension nutrient sufficiency ranges for plant tissue analyses for cotton. (https://aesl.ces.uga.edu/publications/plant/Cotton.html).

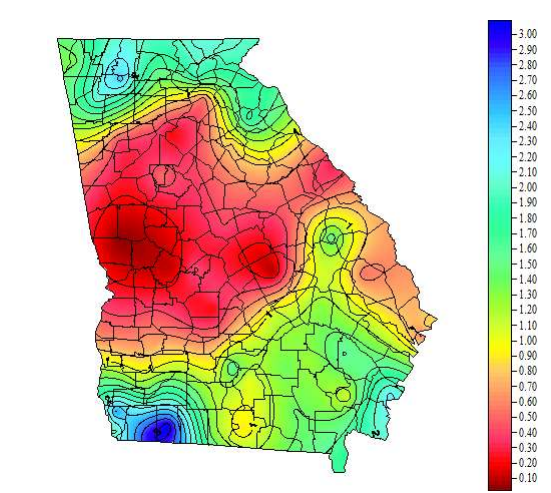

Planting Considerations Following a Much Needed Rain (Camp Hand): As we enter full swing for cotton planting here in Georgia, I am very thankful we do not find ourselves where we were this time a year ago. The vast majority of the cotton producing regions of our state received measurable rainfall on April 27, with more forecasted in the coming days (I am writing this April 28 because we will be planting nearly every day next week). Rainfall accumulation across the state as recorded by the UGA Weather Monitoring Network is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Rainfall across Georgia on April 27, 2023 (Data from the UGA Weather Monitoring Network).

This rain could not have come at a better time. Many are itching to begin planting, and this rainfall signifies a “green light” of sorts to get started. I spoke with someone a couple of weeks back and they asked what cotton growers in Georgia should be thinking about right now. In my opinion, what I would be thinking about right now is taking advantage of this moisture, particularly in dryland fields. We all know that May and early June tend to be dry in South Georgia, so this could be the last significant rainfall we see for a while. Although I believe that planting into adequate moisture might be the most important consideration for stand establishment right this second, there are a couple of other things to consider.

One great tool in deciding when to plant based on forecasted air temperatures is the North Carolina State University Cotton Planting Conditions Calculator. Utilizing this tool, you can look at forecasted 5-day DD-60 accumulation (based on air temperatures) in your individual fields by finding them on a map, and the calculator will tell you how the planting conditions are based on the 5-day DD-60 accumulation ranging from poor conditions (10 or fewer DD-60s in 5 days) to excellent conditions (45 or more DD-60s in 5 days). I use this tool frequently for deciding when to plant my early cotton (~April 1), particularly when I am trying to hit a marginal to adequate window to stress emerging cotton, and I find it extremely useful in making planting decisions early in our planting window. However, from this point forward I believe the temperatures that are forecasted will show that planting conditions according to this model will be good to excellent for the vast majority of South Georgia.

If you intend on planting cotton in the Northern parts of Georgia this tool can still be extremely helpful as temperatures begin to rise into May. As we all know, the weather forecast can change rapidly this time of year, so if you decide to use the planting conditions calculator, it wouldn’t hurt to check in the morning and then again in the afternoon to make sure that predicted planting conditions have not been drastically altered by weather forecasts.

Another factor in stand establishment to consider is seed quality. This is a topic that myself and other cotton agronomists across the belt have dedicated a great deal of time to the last few years. In Georgia, we are extremely blessed to have a wide planting window, meaning that air and soil temperatures aren’t our most limiting factor with respect to stand establishment (most of the time). However, in other parts of the cotton belt, producers must get their crop planted in a 10 to 14 day window because they will run out of time on the back end. Seed quality becomes extremely important with respect to a tight planting window, as growers will likely be planting into less than ideal conditions. However, this does not make Georgia growers immune from seed quality issues. The two major indicators of seed quality that seed companies measure are warm germination or standard germination tests, as well as cool germination. Warm or standard germination is typically indicative of how the seed will germinate in ideal planting conditions, while cool germination is more indicative of how the seed will germinate in less ideal conditions. Seed companies test for both of these measures and each seed lot is individually tested. Thus, if you intend on planting soon and would like these measures, they can be obtained from your local seed company representative.

If you have yet to make a decision on which variety to plant, UGA on-farm variety trial results for 2022 are available .

Although many factors affecting stand establishment have been discussed here, I want to reiterate that we should ALWAYS plant into good moisture – whether we are farming irrigated or dryland ground. Let’s take advantage of what the good Lord has given us and roll on. Be safe out there, and as always, if you have questions please don’t hesitate to reach out. Your local UGA County Extension Agent and members of the UGA Cotton Team are here to help!

UGA Weather Network and Stand Establishment in East Georgia Cotton (Wade Parker): This is my first submission to the monthly UGA Cotton Newsletter. I appreciate the opportunity to submit as I learn the ropes of this new position and figure out different means of information delivery.

At the time of this submission, it is the first of week of May and with that comes the urge for growers to get started planting. Many in Georgia will plant peanuts first, with cotton not trailing far behind. To assist growers in making planting determinations, I encourage use of the UGA Weather Network. For Southeast District, there are twelve locations evenly dispersed throughout our territory and many more on the border that could be relevant to your county.

Low air/soil temperatures and cotton seed germination can make getting a stand challenging. Early season cotton growth is accelerated when it is 86o F on the hi end and 60o F on the low end. Soil temperatures should be 65o F or higher with at least 50 growing degree days (DD60s) projected to be accumulated for the first five days. Upon looking at the UGA weather data from Midville (as I write this on April 28), the current soil temperatures are 60.5o F and 69.1o F at the two- and four-inch level respectively and the predicted air temperature hi is 81o F and low is 63o F. While not impossible to achieve a healthy growing stand of cotton, these conditions make it tougher as the chance of getting 50 DD60s in the foreseeable future is not as good. In fact, when the minimum and maximum temperatures for the next five days are entered into my DD60 spreadsheet calculator, the number is only 13 DD60s accumulated, which is well below the 50 needed. There is no DD60 predictor on the UGA Weather Network, but you can access past DD60s. For example, on April 27, there was only two DD60s earned. There are other variables to consider in the decision to plant or not plant including: potential for soil crusting, pest issues, rain forecast, waterlogging (especially with areas that were recently hit with strong storms) and even lack of moisture if applicable. Many of these variables can be dealt with through seeding rates, planting depth, and tillage as we shoot for a final stand of 1.5 plants per foot of row. These are just a few examples of how the UGA Weather Network can be used to help you and your growers make good planting decisions.

Early Season Staging of the Cotton Crop (John Snider, Camp Hand, Josh Lee): In the last cotton team newsletter, I discussed ways to simplify early season planting decisions, so growers can ensure that the seed they put in the ground gets out of the ground. Many other members of the cotton team provided valuable information for cotton producers in each of their respective areas of expertise. I perused last month’s newsletter articles and found a wide variety of information addressing planting decisions, planter settings, minimizing drift, early season fertilizer and water applications, thrips management, silverleaf whitefly risk, nematodes and diseases, economics, and La Nina. The diversity of topics covered illustrated the complexities of managing a cotton crop, but as I tried to come away with a common theme that I could use as a basis for my article this month, it came to me. Timing matters!

In fact, timing matters probably more than any other factor I can think of when it comes to managing a cotton crop. For example, thrips management to prevent yield loss is especially important from planting to the four-leaf stage of plant development. Anything that can be done to control nematodes and seedling diseases must be done prior to closing the furrow. In the first month after planting, crop water use is extremely low because plants are small and have very little sun-exposed leaf area to transpire water, so irrigation events will be needed much less frequently than at later growth stages. The “Right Time” is one of the 4Rs of nutrient stewardship, where some nutrients are applied predominantly at planting, and others, like nitrogen, are applied in split applications, one at planting and one between the start of squaring and flowering. Herbicidal weed control, potential for crop injury, and potential to prevent weed induced yield loss depend on crop growth stage. Therefore, it is important that we are all speaking the same language when talking about the growth stage of the cotton crop.

The emergence stage

Since we’re so early in the growing season, let’s start with the “Emergence” stage of crop development. A plant is considered emerged when the cotyledons have cleared the soil surface (no part of the cotyledons are touching the soil). Often, the term “germination” will be used interchangeably with “emergence”, but emergence is the more correct term when talking about the number or density of plants with cotyledons above the soil surface.

What are the cotyledons?

The cotyledons are embryonic “seed leaves” that serve as food storage organs prior to emergence. During the germination process, the energy reserves of the cotyledons are raided by the embryo to drive preemergence growth of the seedling. After emergence, the cotyledons turn green and become photosynthetic machines that drive additional root and shoot growth for the developing seedling. Figure 1 is an image of a cotton field at the emergence stage of crop development with only the cotyledons showing above the soil surface. The cotyledons are not considered “true leaves” and can be distinguished from true leaves in two different ways. 1) The cotyledons are shaped liked kidney beans (or just kidneys if that makes things easier to remember). 2) There will be two cotyledons that occur directly opposite of one another. All true leaves that develop after the cotyledons will show up in an alternating pattern up the main stem.

Figure 1. Cotton cotyledons above the soil surface at the emergence stage of crop development.

The nth leaf stage

I’m aware the “nth” doesn’t immediately mean much to anyone reading this newsletter, including me. However, everyone reading this has probably heard someone refer to cotton as being in the 1st true leaf stage, the 4-leaf stage, 6-leaf stage, etc. The “nth” above simply refers to the number of true, mainstem leaves on a cotton plant. The nth leaf designation is normally only used to refer to development in the early stages of growth prior to squaring because after squaring, the plant exhibits a complex branching pattern that would make characterization based on the number of true leaves unrealistic and uninformative. Figure 2 below shows a cotton crop in the 2-leaf stage of development that was planted back in mid-April. Note that we only count unfurled “true leaves” when staging cotton based on leaf number. The first true leaves will alternate up the main stem and will be somewhat heart shaped (envision a Valentine’s day heart rather than a muscular, closed-circuit blood pump). Note that we do not count the cotyledons in the number of mainstem leaves. Once the cotton crop begins producing squares (floral buds), management considerations and the terminology used to define crop growth stage will change. I’ll cover that in the June newsletter.

Figure 2. Cotton seedling in the two-leaf stage of crop development.

Weather and Climate Outlook (Pam Knox): While we had an early start to the growing season, it was followed by colder conditions in March that slowed things down quite a bit. Since that time, we have seen periods of very warm weather alternating with much cooler conditions. I know it’s been frustrating for farmers as soil temperatures rise and fall, making it tough to know when to plant. Wet conditions have also been an issue in some areas.

The current cool weather is expected to stick around until early May, but after that the extended outlook shows a likely return to warmer than normal conditions for much of the growing season. We expect there will be occasional cooler periods, but the warmer conditions should help crops catch up on growing degree days and most should start developing at a more rapid pace than they are right now. The extended forecasts at the moment do not indicate any extended period of very dry conditions, so I am hopeful that we may escape a big drought this summer in spite of the warmer than normal temperatures. The big player in the weather the rest of this growing season and next winter is the rapidly developing El Niño. El Niño is likely to be declared in the next few months. The odds currently put our chances of a strong El Niño by fall at 40%, with an almost 70% chance of at least a moderate El Niño and only a 10% chance of no El Niño at all. El Niño does not have a lot of impacts on Georgia in the summer months, but by fall it will start to impact conditions here in Georgia and surrounding areas.

The statistics and the longest-range climate models suggest that by November we could see typical rainy El Niño conditions occurring over southern GA and AL down into Florida as well as up the East Coast. Some models have wet conditions starting already in October. For farmers, this means that you will not necessarily be able to count on a dry fall for harvesting. David Zierden, the Florida State Climatologist, says that you may wish to plant varieties that will mature more quickly so you can harvest before the wet conditions really get entrenched later in the fall. If your crops are already in, then you will want to be watching the weather forecasts carefully this fall to take advantage of any dry windows that you can to get in the fields and take care of the harvest. This is probably not going to be a year where you can leave crops out in the field without taking a hit on quality and the ability to harvest late due to potentially wet weather and poor field conditions.

The other consideration for an El Niño is its impact on the Atlantic tropical season. Generally, when an El Niño is in place, the strong jet stream aloft makes it hard for tropical storms to organize and so we typically have fewer named storms in El Niño years. But that does not mean that we won’t see any impacts. Remember, Hurricane Andrew developed at the end of an El Niño in 1992 and Hurricane Michael formed as the last El Niño episode was starting in fall 2018. It just depends where the storms go, and that is not predictable on a seasonal basis. Since the Gulf of Mexico has sea surface temperatures that are quite a bit warmer than normal for this time of year, I would not be surprised if we saw an early start to the tropical season with storms coming in from the Gulf. Some may develop quickly due to the warm water. Later in the summer and into fall, when El Niño is stronger, the number of storms in what is usually the most active part of the Atlantic tropical season might be lower than in past years.

Early Season Irrigation Requirements for Cotton Production (Wesley Porter, David Hall, Jason Mallard, Phillip Edwards, and Daniel Lyon): While every year brings different challenges, we must closely monitor the weather, soil moisture conditions, and future forecasts and make necessary adjustments. We have had dry conditions during most of April especially in southern Georgia; however, we did receive some significant rainfall during the last weekend of April. While, it can change, and you cannot put too much faith in a 10+ day forecast, currently the long-term forecast is for us to dry back out after the first of May with less than a 30% chance of rain until mid-May. Currently, the temperatures are expected to remain in the 80’s during the foreseeable forecast. However, in the recent years it has turned hot and dry during the month of May. Knowing this, we need to plan for planting into dry conditions and should plan to apply a small amount of irrigation prior to planting to initiate germination if possible in irrigated fields. It is also important to note that in order to receive the maximum benefits from recommended pre emerge chemicals, another irrigation application should be planned. This of course is depending on expected weather. It has been documented that cotton seedlings receive less damage if the chemicals are incorporated with around 0.5 inch of water soon after the radical has formed but before emergence. This is a tight window so be prepared to be timely.

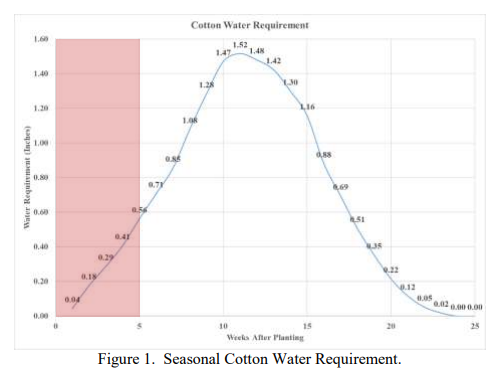

Most of the cotton across Georgia should be planted during early- to mid- May. Similar to peanut, cotton does not require very much irrigation during the first month or so of growth and in some cases, if adequate rainfall is received, cotton can go up to squaring and even bloom without additional irrigation applications as exhibited by the red box and water use curve below in Figure 1. UGA Extension has developed an Irrigation Reference Guide for Corn, Cotton, Peanuts, and Soybeans | UGA Cooperative Extension, a quick and easy irrigation scheduling guide that is laminated and contains the four major row crops grown in Georgia. However, if it gets hot and dry again like it did during late May and early June of 2021 and 2022 you may need to apply a few small irrigation applications either weekly or potentially a few times per week. The red box below represents cotton water requirements the first five weeks after planting. Keep a track of rainfall and temperature, your irrigation efficiency (typically around 65-70% for high pressure systems and 80-90% for low pressure systems), and make irrigation applications accordingly. Keep in mind that the water requirement in the figure is irrigation plus rainfall, and the weekly water requirement recommendation was developed based on a historical average evapotranspiration. Thus, your actual water/irrigation requirement may vary slightly based on weather conditions and rainfall during the growing season. For a more in-depth irrigation recommendation it is suggested that you look into implementing either a computer scheduling model either online or via a Smartphone App, or soil moisture sensors.

For cotton farmers who utilize tools such as soil moisture sensors in their irrigation scheduling, there are a few quick reminders to keep in mind. We tend to visualize the above ground plant biomass and forget what is growing below the surface. We can sometimes be guilty of placing a sensor in the row of the cotton let it start logging data, making decisions from that data and assuming everything is good to go. Unfortunately, we need to ensure we know what is going on in the field before we blindly start following the sensor. Based on when you planted certain fields, cotton may be spread in age by several weeks while some is still in the bag, this is a good time to think about “weighting sensor depths” according to rooting depths.

Weather and available moisture are constant variables. Adding rooting depths and plant needs in the equation creates the need for a formula for weighting sensor depths in your irrigation scheduling decision, an important factor throughout the growing season. Most sensors come with two or three depths that measure available moisture. Early in the season, we generally have cool nights and afternoon temps are “normally” around the low to mid 80s. The evaporation rate is low in comparison to the dry hot summer days and nights. The root profile for the first month develops fairly shallow in the soil. These combinations of events reflect the plant water needs, as shown in our UGA Checkbook method. Moisture sensors generally default to an average of sensors available on the probe for a trigger decision. This can suggest we irrigate when it isn’t needed for young cotton plants. For example, if a 16” depth is showing a dry reading and the 8” sensor is reading adequate moisture, the average will possibly trigger an irrigation event. If a cotton plant has just fully emerged and your root profile is in the 8”-10” range in this scenario, you actually do not need to irrigate. Now, considering the rooting depth let’s weight the 8” sensor by an 80% value and the 16” sensor by 20%. Now since the average is weighted higher on the shallow sensor it can be seen that irrigation may not be needed. You should not begin to fully use deeper sensors for irrigation scheduling decisions until you see water use is occurring at those depths. Weighting moisture sensors can be very beneficial but can be harmful if adjustments are not made during the growing season. If you are interested in weighting sensors, below are UGA Extension suggestions to consider for weighting sensors during the growing season:

D1 = shallow sensor D2 = middle sensor D3 = deepest sensor

- Early-Season: 80% * D1, 20% * D2, 0% * D3

- Early-Mid Season: 60% * D1, 30% * D2, 10% * D3

- Mid-Season: 50% * D1, 25% * D2, 25% * D3

- Late-Season: 40% * D1, 30% * D2, 30% * D3

Soil moisture sensors provide the most accurate means of monitoring available soil moisture. Monitoring the root zone and available moisture present is a great tool in irrigation scheduling.

Early Season Nematode Update for 2023: Make Careful Decisions Before Closing the Furrow (Bob Kemerait): Whether one puts much importance on a “3-peat” of a warmer-than-average La Niña winter or not, the prudent thing for cotton growers to do now is to consider the threat from nematodes in 2023. Already corn growers across the state have experienced the consequences of not using a nematicide; cotton growers should be careful in their plans for effective nematode management.

The peak of cotton planting is upon us and cotton growers are reminded that careful decisions made now are critical to protecting the crop and yield potential for the rest of the season. Nematodes, especially rootknot, reniform, and sting, can cause serious damage to a cotton crop. The best, and sometimes the only, management options are spent once the furrow is closed. Where root-knot and/or reniform nematodes are an issue, growers are reminded that they can plant nematode resistant varieties. Planting resistant varieties will protect the plants from damage without the use of nematicides and will also help to reduce growth of nematode populations that will affect the cotton crop next season. Examples of nematode resistance cotton varieties for 2023 include DP 2141NR B3XF (root-knot and reniform resistance), PHY 443 W3FE (root-knot, reniform, bacterial blight resistance), PHY 411 W3FE (root-knot, reniform, and bacterial blight resistance), DG 3644 B3XF (root-knot and reniform resistance) and ST 5600 B2XF (root-knot nematode). There are also other varieties that have only resistance to root knot nematodes.

Growers who choose not to plant nematode-resistant varieties, for whatever reason, are encouraged to use nematicides judiciously. No nematicide can provide season-long protection to the cotton crop and certainly will not any effect on nematode populations for next season. (Only planting resistant varieties or rotating away from cotton to a non-host crop will reduce populations for next season.) However, use of an appropriate nematicide at the appropriate rate will allow a cotton plant to get a “head start” and begin to develop a robust root system before the inevitable damage occurs. Protecting that young root system for 4 to 6 weeks early in the season can have lasting benefit on yield and profit. Below are several key points to getting the most out your investment in use of a nematicide:

- Know the type of nematodes and the size of the population in your fields. This is best

accomplished with samples taken after harvest in the previous season. However, because of the

generally warm winter of 2022-2023, soil samples taken now before planting may be helpful in

the decision to plant a nematode resistant variety or to use a nematicide. Some nematodes, such as

the ectoparasitic sting nematode, may be an easier target because they stay outside the root and are

more exposed to the nematicide. Knowing the population size helps to determine which

nematicide, fumigant (Telone II), granular (AgLogic 15G), liquid (Velum), or seed treatment (e.g.

AVICTA, Copeo, BIOst, or Trunemco) is likely to best provide the needed protection to the cotton

crop. - Averland FC nematicide (active ingredient abamectin) is a new product for 2023. As there is very

little data available for the efficacy of Averland at this time, growers should use caution before

whole-scale replacement of products that have proven effective in the past. UGA Extension will

have additional data on Averland FC after the 2023 season. - Once the furrow is closed, the only additional option for nematode management available to

growers in a foliar application of oxamyl (Vydate-CLV or ReTurn XL) at about the 5th true leaf

stage to possibly extend the protective window of nematicides applied at panting. - As noted above, nematode problems for corn growers have been widespread again in 2023. I

suspect that the combination of a warmer “La Niña” winter coupled with corn-behind-corn has led

to such problems. Cotton growers should also anticipate increased problems with nematodes in

2023 for similar reasons. - Getting the most out of a nematicide requires using the right product at the right rate. It also

requires consideration for environmental conditions as well. For example, fumigation with Telone

II is affected by soils that are too wet or too dry at time of application and by significant rain

events after fumigation. Likewise, granular products such as AgLogic 15G require some soil

moisture to be activated and also taken up into the roots.

Early Season Nematode Update for 2023: Make Careful Decisions Before Closing the Furrow (Bob

Kemerait): Whether one puts much importance on a “3-peat” of a warmer-than-average La Niña winter or

not, the prudent thing for cotton growers to do now is to consider the threat from nematodes in 2023.

Already corn growers across the state have experienced the consequences of not using a nematicide;

cotton growers should be careful in their plans for effective nematode management.

The peak of cotton planting is upon us and cotton growers are reminded that careful decisions made now

are critical to protecting the crop and yield potential for the rest of the season. Nematodes, especially root-

knot, reniform, and sting, can cause serious damage to a cotton crop. The best, and sometimes the only,

management options are spent once the furrow is closed. Where root-knot and/or reniform nematodes are

an issue, growers are reminded that they can plant nematode-resistant varieties. Planting resistant varieties

will protect the plants from damage without the use of nematicides and will also help to reduce growth of

nematode populations that will affect the cotton crop next season. Examples of nematode resistance

cotton varieties for 2023 include DP 2141NR B3XF (root-knot and reniform resistance), PHY 443 W3FE

(root-knot, reniform, bacterial blight resistance), PHY 411 W3FE (root-knot, reniform, and bacterial

blight resistance), DG 3644 B3XF (root-knot and reniform resistance) and ST 5600 B2XF (root-knot

nematode). There are also other varieties that have only resistance to root-knot nematodes.

Growers who choose not to plant nematode-resistant varieties, for whatever reason, are encouraged to use

nematicides judiciously. No nematicide can provide season-long protection to the cotton crop and

certainly will not any effect on nematode populations for next season. (Only planting resistant varieties or

rotating away from cotton to a non-host crop will reduce populations for next season.) However, use of an

appropriate nematicide at the appropriate rate will allow a cotton plant to get a “head start” and begin to

develop a robust root system before the inevitable damage occurs. Protecting that young root system for 4

to 6 weeks early in the season can have lasting benefit on yield and profit.

Below are several key points to getting the most out your investment in use of a nematicide:

- Know the type of nematodes and the size of the population in your fields. This is best

accomplished with samples taken after harvest in the previous season. However, because of the

generally warm winter of 2022-2023, soil samples taken now before planting may be helpful in

the decision to plant a nematode resistant variety or to use a nematicide. Some nematodes, such as

the ectoparasitic sting nematode, may be an easier target because they stay outside the root and are

more exposed to the nematicide. Knowing the population size helps to determine which

nematicide, fumigant (Telone II), granular (AgLogic 15G), liquid (Velum), or seed treatment (e.g.

AVICTA, Copeo, BIOst, or Trunemco) is likely to best provide the needed protection to the cotton

crop. - Averland FC nematicide (active ingredient abamectin) is a new product for 2023. As there is very

little data available for the efficacy of Averland at this time, growers should use caution before

whole-scale replacement of products that have proven effective in the past. UGA Extension will

have additional data on Averland FC after the 2023 season. - Once the furrow is closed, the only additional option for nematode management available to

growers in a foliar application of oxamyl (Vydate-CLV or ReTurn XL) at about the 5th true leaf

stage to possibly extend the protective window of nematicides applied at panting. - As noted above, nematode problems for corn growers have been widespread again in 2023. I

suspect that the combination of a warmer “La Niña” winter coupled with corn-behind-corn has led

to such problems. Cotton growers should also anticipate increased problems with nematodes in

2023 for similar reasons. - Getting the most out of a nematicide requires using the right product at the right rate. It also

requires consideration for environmental conditions as well. For example, fumigation with Telone

II is affected by soils that are too wet or too dry at time of application and by significant rain

events after fumigation. Likewise, granular products such as AgLogic 15G require some soil

moisture to be activated and also taken up into the roots.

Though the 2023 cotton season is in its infancy, protecting a cotton crop against nematodes now will have

lasting benefit throughout the season. Growers are encouraged to make the best management decisions

now.

Supplemental Control of Thrips with Foliar Insecticides (Phillip Roberts): Thrips infest near 100 percent of Georgia cotton each year. At-plant insecticides which are recommended as a preventive treatment for thrips control provide a consistent yield response. At-plant treatments include aldicarb applied as granules infurrow, imidacloprid or acephate applied infurrow as a liquid, or neonicotinoid and/or acephate seed treatments. Infurrow treatments provide improved control and longer residual compared with seed treatments. ThryvOn is a new transgenic trait which greatly reduces thrips injury. Management of thrips in ThryvOn cotton will be covered in another section of this newsletter. Comments below pertain to thrips management in non ThryvOn cottons.

Thrips begin infesting cotton as it emerges. Initially adult thrips feed on the underside of the cotyledons. Feeding injury is recognized by a silvery sheen on the bottom of the cotyledon. Adult thrips also deposit eggs in the cotyledon tissue. Thrips eggs will hatch in 5-6 days. Once the terminal forms thrips will move to and feed on unfurled leaves in the terminal. As these leaves unfurl, the characteristic crinkling and leaf malformation becomes obvious. Thrips injury is compounded by slow seedling growth. Therefore, if seedlings are stressed due to cool temperatures or herbicide injury, be sure you scout thrips and be timely with foliar sprays if needed. Thrips infestations are generally higher on early planted cotton compared with later planted cotton. Historically we use May 10th as the line separating high risk and low risk. However, this date is a moving target from year to year. The Thrips Infestation Predictor for Cotton is a web-based tool which predicts thrips risk by location and planting date.

Scout thrips by randomly pulling plants at several locations and slapping the individual plants on a piece of paper to dislodge the thrips. Thrips will begin to move in a few seconds and count both adult and immature thrips. Adults thrips have wings and are generally brown to black in color. Immature thrips are cream colored and lack wings. The threshold for thrips is 2 to 3 thrips per plant with immatures present.

The presence of immature thrips is important as this indicates the at plant insecticide is no longer providing control. It is also important to observe true leaves, especially the newest leaf unfurling. If excessive damage is present you probably have lots of thrips. Seedlings in early stages of development (i.e. 1-2 leaf) are more sensitive to thrips feeding in terms of yield compared with 3-4 leaf cotton. If you have a thrips problem on 1-2 leaf cotton it is worth a special trip to control thrips! Once cotton reaches the 4-leaf stage and is growing rapidly, economic loss from thrips is rarely observed. Growing rapidly is important when making the decision to no longer worry about thrips. Orthene, Bidrin, and dimethoate are recommended for foliar treatment of thrips. When evaluating the performance of a foliar spray, remember that the next leaf to unfurl will still be damaged since thrips were feeding and damaging the unfurled in the terminal prior to the spray.

Thrips Management in ThryvOn Cotton (Phillip Roberts): ThryvOn is a new transgenic trait which significantly reduces thrips injury. We have conducted field trials with ThryvOn for several years and have never observed a planting which would benefit from a supplemental foliar insecticide. ThryvOn does not result in high levels of thrips mortality, however thrips feeding and egg laying are significantly reduced. Typically, we observe about a 50 percent reduction in actual thrips numbers when scouting and sometimes we observe populations exceeding the threshold in non-ThryvOn cotton. However, we rarely see significant plant injury even if very high thrips infestations are present. For this reason, it is important that we DO NOT make decisions to treat ThryvOn for thrips based on insect counts. The threshold for thrips on ThryvOn cotton is treat if excessive plant injury and immature thrips are present. Again, based on research in Georgia and across the Cotton Belt, we do not expect ThryvOn cottons to require supplemental foliar sprays for thrips. It is important that we do not confuse thrips injury with other confounding symptoms associated with herbicide injury or sand blasting. Dr. Scott Graham, Auburn Extension Entomologist, in cooperation with Extension Entomologists across the Southeast recently published Maximizing Insect Control in ThryvOn Cotton in the Southeast.

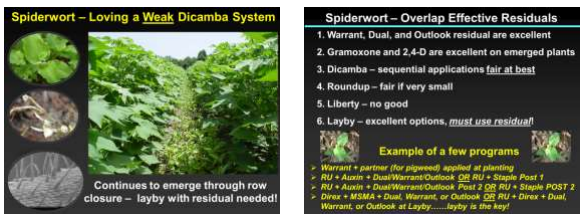

Carefully Manage Benghal Dayflower aka Tropical Spiderwort or Watch It Spread! (Stanley Culpepper): For three years in a row, tropical spiderwort has regained its status of being a major pest for many Georgia cotton farmers. The main reason for the weed to be on the move once again is likely due to the adoption of “weak” dicamba systems underutilizing effective residual herbicides and the lack of applying conventional chemistry as a layby directed spray. Interestingly for those who hate to slow down and take the time to run a layby rig or hooded sprayer through the field as cotton nears row closure, this weed along with morningglory has the potential to be your kryptonite.

Tropical spiderwort is a federally noxious, exotic weed that can spread quickly. Upon initial observation, tropical spiderwort appears to be a grass. While not a grass, it is a monocot (in contrast to broadleaf weeds, which are dicots) with leaves and stems usually fleshy and succulent. The stems will creep along the ground and root at the nodes. Vegetative cuttings from stems are capable of rooting and reestablishing following cultivation. Tropical spiderwort will produce seed above and below ground. As of last week, spiderwort was present in some South Georgia fields and is expected to emerge more aggressively moving into early May with emergence potentially lasting through frost, even after cotton row closure.

To be successful, one must understand the importance of placing effective residual herbicides strategically throughout the growing season starting at planting. Numerous effective programs exist as long as one understands the concept of overlapping residual herbicides and is timely with those applications; a few program examples are provided in the figure below. As always follow all herbicide label restrictions.

Important Dates:

Georgia Cotton Commission Mid-Year Meeting – Statesboro, GA – July 26, 2023

Southeast Research and Education Center Field Day – Midville, GA – August 9, 2023

Cotton and Peanut Research Field Day – Tifton, GA – September 6, 2023

Georgia Cotton Commission Annual Meeting and UGA Cotton Production Workshop – Tifton, GA – January 31, 2024