Most growers have peanuts that are around 100 days after planting. This is the time we generally start checking for maturity to determine how many days are left until digging.

There are a few important things to consider when collecting a peanut maturity sample. Remember, the projected digging date is only as accurate as the sample used to represent the field.

For sampling peanuts, carefully lift at least 5 plants from a minimum of three representative areas in a field.

If a field has two soil types it needs to be split and sampled as two fields. Irrigated fields need to be sampled separately from the dry corners.

Each sample should represent no more than about 25 acres, so large fields may need to be split into 25 acre sections with a sample for each section. Each field should be sampled at approximately 105 to 110 days after planting. A second sample should be done approximately 10 days before the date predicted by the first check to determine if the peanuts are maturing normally. This process has proven to be an effective and reliable method to project up to two weeks in advance the optimum digging date for peanuts.

To get a good representative sample of the field, collect plants from several spots, but no bottoms or diseased or skippy areas. It takes about 200 peanuts per sample.

I have noticed some peanuts coming loose in the hull in some earlier peanuts I sampled. That’s why it’s critical to open some of the peanuts being checked to see if they are still attached.

There are a few other tools to assist with determining maturity. The University of Florida has the PeanutFARM Peanut Field Agronomic Resource Manager website here. I’ve used it to check some of my research plots and a few grower fields and it works well.

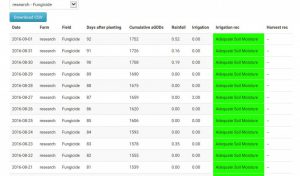

The program uses weather station data and field info entered by the farmer to determine adjusted growing degree days. You can enter as many farms and fields as you need and select the weather station closest to each field. Based on research, 2,500 adjusted growing degree days is near maturity for most peanuts we grow.

In order to get accurate growing degree days, the irrigation rates for irrigated fields must be entered. The below picture is from the same field as above, but I entered irrigation dates and rates. This significantly changed the growing degree days.

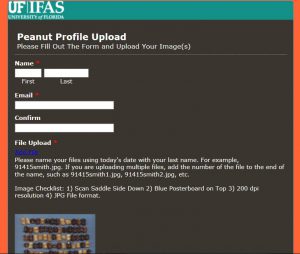

You can also upload a picture of the peanuts once they have been pressure washed. Within 24 hours (mine usually takes 15 min.) an email will be sent to you with the number of days until digging.

The peanuts must be laid out with the saddle up and a blue background, or scanned saddle side down with a blue background. You can’t just pour them out on a truck tailgate and take a picture. The time must be taken to lay the peanuts out correctly or the results won’t be accurate.

Below is a picture from one sample I’ve sent in. I used a lid from a plastic container and took the picture with my phone. When I checked this sample on the profile board I estimated it was about 21 days from digging. I sent the picture in and their estimate was 25.4.

This doesn’t eliminate the need for having an experienced person check your peanut samples. However, it does give us another tool and a way to double check recommended digging dates. If the UF Peanut website recommends 10 days until digging, and a person checking the sample on a profile board said it was 21 days until digging, something is wrong.

Keep in mind that over 200 lbs. of peanuts can be lost due to digging early or late.

When Should You Terminate Fungicide Sprays?

Below are some typical situations that peanut growers may find themselves in and suggestions for control:

-Grower is 4 or more weeks away from harvest and currently has excellent disease control.

1. Suggestion – Apply at least one more fungicide at least for leaf spot control.

2. Suggestion – Given the low cost of tebuconazole, the grower may consider applying a tank-mix of tebuconazole + chlorothalonil for added insurance of white mold and leaf spot.

3. NOTE: If white mold is not an issue, then the grower should stick with a leaf spot spray only.

-Grower is 4 or more weeks away from harvest and has disease problems in the field.

1. If the problem is with leaf spot – Grower should insure that any fungicide applied has systemic/curative activity. If a grower wants to use chlorothalonil, then they would mix a product like thiophanate methyl (Topsin M), cyproconazole (Alto), with the chlorothalonil. Others may consider applying Priaxor, if they have not already applied Priaxor twice earlier in the season.

2. If the problem is white mold – Grower should continue with fungicide applications for management of white mold. If they have completed their regular white mold program, then they should extend the program, perhaps with a tebuconazole/chlorothalonil mix. If the grower is unhappy with the level of control from their fungicide program, then we can offer alternative fungicides to apply.

3. If the problem is underground white mold – Underground white mold is difficult to control. Applying a white mold fungicide ahead of irrigation or rain, or applying at night, can help to increase management of this disease.

-Grower is 3 or less weeks away from projected harvest and does not currently have a disease issue. Good news! This grower should be good-to-go for the remainder of the season and no more fungicides are required.

-Grower is 3 or less weeks away from harvest and has a problem with disease.

1. If leaf spot is a problem and 2-3 weeks away from harvest, a last leaf spot fungicide application may be beneficial. If leaf spot is too severe, then a last application will not help.

2. If white mold is a problem and harvest is 3 weeks away, then it is likely beneficial to apply a final white mold fungicide. If harvest is 2 weeks or less away, then it is unlikely that a fungicide will be of any benefit.

3. NOTE: If harvest is likely to be delayed by threat from a hurricane or tropical storm, then the grower may reconsider recommendations for end-of-season fungicide applications.

**Check labels for preharvest intervals. Some fungicides need 30 or more days before harvest.

Contributors: Dr. Bob Kemerait, UGA