The older I get, the more I realize that the “spooky” motifs associated with Halloween are just normal things we see in nature and agriculture at this time of year. Summer-planted pumpkins ripen in the fall. Bats increase feeding behavior to prepare for winter hibernation. Autumn begins “hooting season” for owls, as they become more vocal to establish territories and find mates for next spring’s breeding season. And yes, spiders seem to be everywhere this time of year.

Aside from Joro spiders – a recently introduced species that ramp up activity in September and October (more on them later) – our native spiders seem to surge in fall. Why?

Seasonal Behavior

As days shorten and temperatures drop, spiders actively search for food to prepare for winter. Many spider species are univoltine, meaning they only have one generation per year. In fall, these females are carrying developed eggs and looking for somewhere protected to deposit them for the winter. If all goes according to plan, the eggs will overwinter without being destroyed or eaten by predators, and baby spiders (called spiderlings!) will hatch in the spring. These gravid females with inflated abdomens are often much larger than males of the same species, and the largest they themselves will be all year.

Some spiders make their way into homes and buildings in the fall, looking for a warm, protected place to spend the winter.

What makes spiders frightening?

Why do we find spiders creepy anyway? Research tells us that a fear of spiders is one of the most common animal phobias, and scientists have conducted all sorts of experiments to get to the bottom of why spiders elicit such strong responses in people.

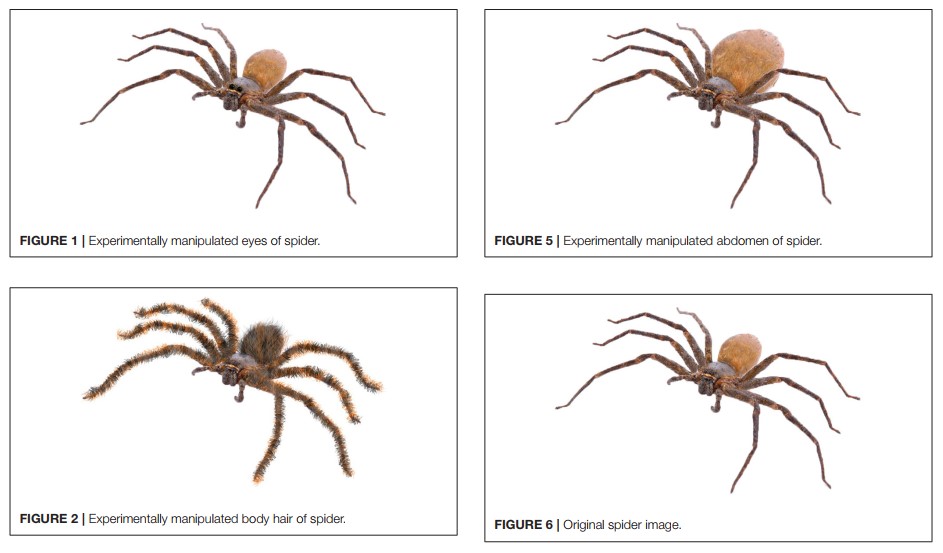

Several studies showed that the negative reactions people with arachnophobia experience are not just feelings of fear, but also of disgust. One research paper digitally “enhanced” different physical features in an image of a spider and showed it to participants to see if a particular body part was most fear-inducing. They found that the scariest features of a spider body were the abdomen, followed by the chelicerae, the paired appendages that function as mouthparts. Respondents were also more frightened by images with hairy spiders than those without hair.

Another study found that arachnophobia is not a general fear of all small arthropods. Spider fear is in fact spider-specific, and spiders elicit significantly greater fear and disgust than any other group of arthropods.

Some experts cite the “preparedness hypothesis,” which claims that fearing spiders is a biological asset because it helps us identify and avoid threatening or dangerous animals. Other experts say the preparedness hypothesis doesn’t hold up to scrutiny because only a very small proportion of spiders are really dangerous to humans. If the preparedness hypothesis were true, then people would be equally (or more) scared of bees and wasps because they are statistically more harmful than spiders. Instead, participants in several studies were significantly less fearful of bees and wasps and estimated them to be less dangerous than spiders.

Regardless of what the scientists say, all these spiders in the fall freak me out!

Spider Basics

Even if you are freaked out by spiders, they are critical members of our native food webs. It’s helpful to know a little bit about them and the roles they play in our ecosystems.

All spiders are arthropods (Phylum Arthropoda), further classified in Class Arachnida (arachnids, including scorpions, ticks, mites, and more) and Order Araneae (spiders). Scientists estimate that spiders evolved around 375 million years ago and have described over 40,000 species of spiders across the world.

Most spiders are nocturnal, meaning they’re active at night. Have you ever shone a flashlight around at night and seen lots of little shiny glimmers of light? That’s light reflected off of spiders’ eyes! Some species are diurnal, or active during the day. For example, jumping spiders are active hunters and can be seen searching for prey in the daytime.

Most spiders are also terrestrial, meaning they live on land. However, there are actually some aquatic spiders! Most of these, though, are active on areas around water, not actually under the surface. These species search for prey at the waters edge, construct webs next to the water, or skim for insects on the surface using surface tension. Some, like diving bell spiders, will dive for short periods of time to search for underwater prey, sometimes encasing their abdomen in an air bubble!

Spiders have a few anatomical features that help them succeed in their habitats. They have 0-12 eyes, the number and arrangement of which differs by species. All eyes are used for vision, but not all eyes see in the same way. Typically, the eyes most central to the spider’s face are used to detect the size, shape and color of nearby objects. Eyes further to the sides of the head detect motion. Some spiders have better eyesight than others. Among the spiders with good eyesight are active hunters, like wolf spiders, flower spiders, and jumping spiders.

Spiders also have the ability to produce silk! Silk starts as a liquid protein inside special glands in the abdomen, then turns to dry fibers outside the body. Silk is extruded through spinnerets, which can modify pressure to alter the thickness, strength, and stretchiness of the silk produced. Silk-producing spiders will deposit little droplets of glue along the length of silk using other glands, causing the silk to stick at certain places as they create their webs.

Fun fact: Most spiders ingest their webs and recycle the materials to make more silk!

All spiders are predators and feed on other animals (prey) as their primary food source. Some species are specialists, only feeding on a certain type of prey. Others are generalists and will feed on whatever they can get their chelicerae on. Still others are scavengers, collecting already dead prey if they can find it.

Spiders in the Environment

Most spiders do their hunting in a few key ways:

Web Spinners

When most people imagine a spider, they see it sitting in the middle of a radial web, Charlotte’s Web-style. Turns out, only a subset of spiders capture prey this way. Those that do use silk to spin prey-catching webs of different designs. Orb-weavers, like the commonly observed yellow garden spider, spin spiral, wheel-shaped webs that are true feats of engineering. Many orb-weavers build a new web each night and deconstruct it before morning.

Some spiders, like the bowl-and-doily spider, build sheet webs. These webs are not tidy spirals, like orb webs, but are unorganized tangles of silk that form a network to ensnare prey. Sheet webs constructed by bowl-and-doily spiders have two parts: the upper section is bowl-shaped, and the lower section is flat, like a teacup and saucer. Prey falls into the bowl, and a patiently waiting spider on the flat section is able to access it easily from underneath.Tangle-web spiders, also called cobweb spiders, construct shapeless tangle webs to catch prey. Familiar sights in corners of basements, pantries, and crawl spaces, species like the longbodied cellar spider build tangle webs.

Some spiders, like grass spiders, construct funnel webs. These are funnel shaped, inviting prey to enter, while the spider waits out of sight at the narrow end. Funnel weavers, or grass spiders, create unique flat webs stretched across the ground or between grasses or plants, with a central entry hole which leads into a narrow funnel-shaped web.

Web-spinning spiders also use silk in other ways: to construct shelters, protect eggs, as as an “anchor line.”

Runners and Jumpers

Some spiders don’t spin webs at all but are active hunters, running down or pouncing on their prey. Spiders in this category often have stout bodies, strong legs for running, jumping, and grasping, and excellent eyesight. These are like the wolves and cheetahs of the arthropod world.

Wolf spiders are a common example. These are active, chasing hunters with relatively large bodies. They have particularly good vision and have a reflecting layer in their main eyes which increases their sensitivity in low light conditions. You will usually see them running and capturing prey along the ground.

Jumping spiders are the largest (and cutest!) family of spiders globally. They are small but very active spiders and have excellent vision with four large, forward-facing eyes.

Ambush and Camouflage

Some spiders opt out of actively chasing down their prey and prefer to sit and wait. These are our ambush predators, often camouflaged to match their surroundings and hide themselves among their habitats.

Green lynx spiders are fairly large but can be easily missed owing to their leaf-like coloration. A 2022 study found that green lynxes can change color to match their surroundings!

Crab spiders are aptly named because of the way they hold up their first pair of legs like crab claws, and because they tend to scuttle sideways like crabs. They wait motionless in flower heads waiting for pollinators to arrive, earning them another common name: flower spiders.

What’s the Deal with Joro Spiders?

Joro spiders have become one of the most abundant and visible spider species in north Georgia landscapes in the last several years. First detected in the US in Georgia in 2014, Joros are native to East Asia. Since their introduction, they have spread to North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee, and populations continue moving outwards.

Joros are orb-weaving spiders, like our native garden spiders, forming large, semi-spiraling webs across walkways and clearings. They have one generation per year and are most visible in September and October, when the large females’ abdomens carry nearly fully developed eggs.

The adult females can be up to a whopping 1.25 inches long. Their abdomen is yellow, with broad blue-green bands on the back and yellow and red markings on the belly side. Their legs are long and black, often with yellow bands and tufts of short hair.

The adult males are much smaller and look quite different. They are approximately 0.25 inches long and brown. Their abdomen is an elongate oval shape with two long, yellowish stripes on both sides and a dark brown stripe in the middle.

Despite their intimidating appearance, Joro spiders are not aggressive or severely venomous. Many ask if they are considered invasive. According to the Joro Watch website, “Invasive means that a species is introduced to a new ecosystem and is or has the potential to cause economic harm, environment harm, or harm to human health. The effect that Joro spiders are having is currently being evaluated by researchers.” Short answer – we don’t know yet if Joros will cause harm or will simply be a nuisance.

What we do know about their natural history is that Joros are generalists, who are likely to eat lots of common types of insects, such as moths, flies, mosquitos, bees, wasps, beetles, and stink bugs.

Should I Kill Joros?

Whether you kill Joro spiders when you find them is up to you. Yes, they are an introduced and rapidly spreading species. And yes, they are a nuisance, especially to folks with spider phobias. These may be good enough reasons for you to decide to control them in your yard or landscape. Diligent control in your landscape, whether by killing them or disrupting their webs, will probably reduce how many you see in that immediate area in the short-term.

However, local control by residents is probably not going to have much of an impact on the overall spread. There is no possibility for eradication at this point.

Researchers are still in the information-gathering phase of their research. You can help us understand what’s going on with Joros by reporting any that you see! The Joro Watch website also has more info on Joros and up-to-date maps on where they are found.

If you have questions about Joros or other spiders this fall, don’t hesitate to contact your county Extension agent!