By Maria M. Lameiras

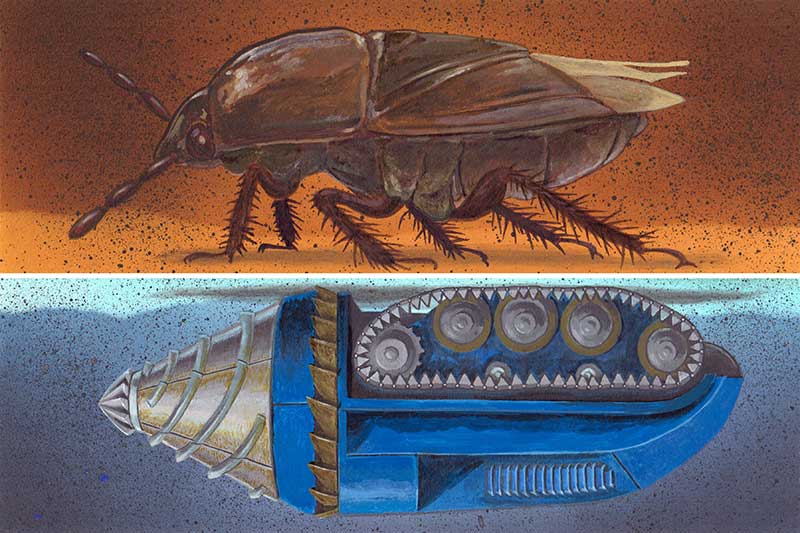

This stylized representation compares a burrower bug to a Jules Verne-style drilling machine. (Illustration by Jay B. Bauer)

The peanut burrower bug is a tricky pest for Georgia’s peanut producers.

Not only is an infestation invisible in a field from above the ground, damage done by the bugs’ piercing mouthparts can only be detected after peanuts are harvested and sent for processing, resulting in unexpected revenue loss.

Working with University of Georgia Cooperative Extension agents, researchers in UGA’s Peanut Entomology Program are working to monitor peanut producers’ fields for the primarily subterranean bugs along with new methods of control. The only pesticide effective against the peanut burrower bug, chlorpyrifos, was banned for use on food products in the U.S. by the Environmental Protection Agency in August 2021.

Sporadic but significant damage

Mark Abney, UGA researcher and Extension peanut entomologist, has been working to address the peanut burrower bug in Georgia since joining the Department of Entomology in 2013.

“Peanut burrower bug is native to our area and to the U.S., but it had not been specifically recognized as a pest in Georgia until 2010. It was first reported as a pest in Texas in the 1970s, but we didn’t hear a lot about it in Georgia, which is the largest peanut producer in the U.S.,” said Abney. Georgia farmers produced 52% of the U.S.’ peanuts in 2021 — more than 1.67 million tons, according to the Georgia Peanut Commission.

Because it is a native species that was not causing damage, no one was paying much attention until the bugs showed up in Georgia in 2010 in a major way.

Every peanut buying point in the state is staffed by inspectors from the Georgia Federal-State Inspection Service, an independent third-party inspection agency that inspects more than 35 commodities in the state, including peanuts.

“A portion is removed from each load that comes into the buying point, and these inspectors started seeing a lot of injury,” Abney said. “You can’t see it on the exterior of the shell, and most of time you can’t see it until the seed coat is removed.”

Related to stink bugs, peanut burrower bugs are “smaller than a pinky fingernail. In the family Cydnidae, they are true bugs, a specific type of insect with piercing, sucking mouth parts. Their mouths are like a hypodermic needle that pierces through the hull of the peanut to the seed — they suck the juice out of the seed,” Abney said. This results in sunken, yellowish, brown or black lesions on the peanut seed, often multiplied due to repeated feedings.

Economically devastating

Because peanuts are rated according to federal regulations, a drop from a segregation 1 rating to a segregation 2 rating — when more than 3.5% of the pods by weight have damage from insects — can mean significant lost revenue for farmers. Segregation 1 peanuts can be used for human consumption either unprocessed or as peanut butter, candy or other food products, Abney said. According to the Georgia Farm Bureau, the regulations were changed in 2018 based on a number of factors, including that “segregation 2 peanuts usually account for less than 1 percent of the U.S. peanut crop, but an individual grower who has his entire crop graded Segregation 2 could face financial ruin.”

“Farmers may deliver trailer loads of a bumper crop, and once the skin on the peanut is removed and the damage is visible, it can be a huge loss,” Abney said. “In today’s dollars in 2022, a ton of peanuts is worth around $500 for segregation 1. Segregation 2 peanuts are worth about $120 per ton. If you have segregation 2 peanuts, you could lose the farm because of all the expense and inputs that go into a crop.”

While peanut burrower bug has not caused as much widespread damage in Georgia since 2010, the potential for damage from the bugs is always present and is difficult to predict and control.

“This is a sporadic pest in that the injury is sporadic. The insect is pretty common. For several years we used light traps all over south Georgia, and everywhere we put a light trap, we would catch peanut burrower bug, no matter where we were or whether there was a history of injury or not,” Abney said. “From a research standpoint, the big, glaring question is why was this such a problem in 2010? And now, why will one grower have a problem with peanut burrower bug, but his neighbor does not? One year a farmer’s peanuts are rated segregation 2, and the next year it doesn’t happen. That has been the focus of a lot of research.”

Limited control methods

Compounding the problem is that solutions to control peanut burrower bug are limited. Aside from the insecticide chlorpyrifos, now banned for use on food in the U.S., peanut burrower bug is controlled through deep tillage — a practice many producers have moved away from in favor of conservation tillage for its environmental and economic benefits.

“The more aggressive the tillage, the lower the risk is of having burrower bug injury. There are a lot of good environmental and economic reasons to use conservation tillage, but a lot of producers have gone back to more aggressive tillage or discing because it is the only tool our growers have since the one chemical tool we had is no longer available,” Abney said. “We’ve looked at virtually every insecticide that is approved for use in peanut — and some that were not — and even if we find that there are insecticides that have activity against the bug, there is no way to deliver it to the populations in the field as they exist.”

In the field, the bugs spend most of their time underground. Because they don’t feed above ground and live underground in the soil, it is difficult both to scout for the bugs and to target with an insecticide, he added. While Abney has worked steadily on the problem since joining UGA, he said it is difficult to perform research on peanut burrower bugs because both finding them in the field and keeping them in lab colonies for testing has been a challenge.

“The population is so sporadic, it is hard to get data on them,” he said.

Counting costs

Ben Aigner, a doctoral student on Abney’s team, is currently working to identify any risk factors that may contribute to the presence of peanut burrower bugs and burrower bug injury in any given year through grants funded by the Georgia Peanut Commission, the National Peanut Board and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

“Ben has a record of nearly all burrower bug injury in the state for four years, then he spoke to growers about what they did in the affected field — crop rotations, management practices, irrigation — and what the environmental conditions were in terms of rainfall. A big part of his job is to put all of that data into a model to explain some of the variations on where burrower bugs are,” Abney said.

While he said there have been no real “Eureka” moments, the team continues to add to the knowledge base about the bugs in the continuing effort to find solutions.

“It tends to be worse in non-irrigated fields, but it can occur in irrigated fields. It can be worse in certain types of soil, but it can be in any type of soil. It would be easy to sensationalize the burrower bug, but the truth is that, more often than not, the problem is limited to a relatively small proportion of the total crop in Georgia year over year,” Abney said. “If growers could get peanut burrower bug insurance, no one would care, but that is not an option. It is truly an existential threat for growers in high-risk areas.”

“Orphan” pest

The most economically important pest in peanuts is lesser cornstalk borer, but only in hot, dry weather. Thrips are the most consistently damaging pest to peanut, followed by rootworms. Abney cannot predict where peanut burrower bugs will fall in the equation from year to year.

“In the United States, there is one person who is a dedicated peanut entomologist, and I am him. There are a few other entomologists who have peanuts as part of their job description in Virginia, North Carolina, Alabama and Mississippi, but the biggest part of their job is focused on other crops,” Abney said. “We have been working to identify alternative (pesticides) for five years for burrower bugs and rootworms.”

While the process can be “infuriatingly slow,” Abney he will continue looking for answers.

“Solving entomological problems for farmers is what makes me happy. There are a lot of farmers whose livelihoods depend on what I do and that is why I do it,” he said.