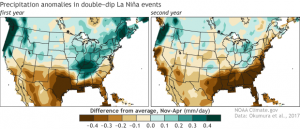

Right now we are in the middle of the second winter of a “double-dip” La Niña. That means that for two winters in a row we have been in La Niña, with neutral conditions in between but no El Niño. This is not that unusual, and we have had several since the 1950s when modern records were started. If we look at the statistics comparing the first and second year of one of these “double-dips”, we find some interesting relationships.

For the Southeast, the most important one for agriculture is that “In terms of U.S. precipitation, the most robust differences identified in the study are found in the Tennessee Valley. Therefore, on the basis of the historical analysis, we may have greatest confidence in the tendency for the Tennessee Valley to be drier in the second winter than in the first.” That means for folks in northern Alabama and Georgia and the western Carolinas, there is a significant chance of drought this coming summer. We’ve already been dry this winter, although the rain today did help alleviate short-term dryness in some areas. But climatologists like me will be watching carefully to see if another drought develops in the coming growing season as the current La Niña dies out.

If you are interested in reading more about it, you can read the latest Climate.gov blog at https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/more-us-drought-second-year-la-ni%C3%B1a.