How do we know what the climate was before official measurements were taken? The historical instrumental records only go back to about the 1820s, when surgeons were the official observers at forts across the United States.

To look at longer-term climate records, you have to use climate markers like tree rings to determine what the climate was. By studying the growth of modern tree species and comparing the ring thicknesses to the climate each year, you can determine what the temperature and precipitation was each year that the tree was alive. If you have trees living through overlapping time periods, you can compare ring patterns and create a serially complete picture of the climate over time. Over longer time periods, other “proxy” data like layers in sediment at the bottom of lakes or oceans can be used to do much the same thing, as well as layers of snow and ice (and volcanic ash) in glaciers and ice sheets like Antarctica. All of these collectively are called “paleoclimate data” and are combined to create long records of the climate on earth much farther back than instruments can do alone.

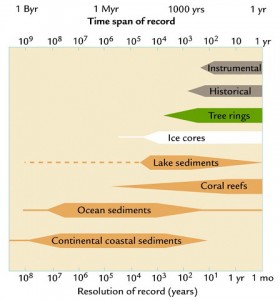

This graph shows the time resolution you can get from various types of proxy data:

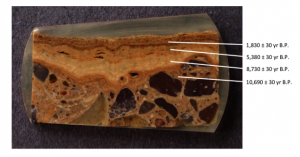

This week the Jornada Experimental Range in New Mexico posted a blog entry describing a new way of measuring climate variations using crusted soils in the desert Southwest (link). The development of these desert crusts is so slow that a slice just 1 millimeter thick contains a record 1000 years long. This is an exciting development because in the past it has been difficult to determine how climate changed in the past due to the lack of trees in the desert. This will give climate scientists new insight into how conditions there have changed over a long time period.