Since we are approaching the end of March and corn is already popping up in South Georgia, it’s time to look at the likely weather conditions for the 2024 growing season. The big factors to consider this year are the rapidly weakening El Niño and predicted quick swing to La Niña, the rising temperatures around the world due to increases in greenhouse gases and decreases in aerosols, and the very warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. The last two years that we had a quick transition from a strong El Niño to La Niña were 1998 and 2016, both years that started out wet due to El Niño but were followed by six months or more of drier than normal conditions.

I will discuss each of these below but here is the bottom line up front: I expect to see lingering El Niño rains and clouds along with cooler temperatures for the next month or two, then a gradual shift to warmer and drier conditions than normal by mid- to late summer, potentially leading to a drought in fall. That may mean a slow start to the planting season but crops should develop more quickly once the warmer weather kicks in.

The biggest wild card in the forecast is how the tropical season will develop this year, since if we get a series of tropical storms over Georgia that will provide enough moisture to overcome the dry conditions. If they go farther west to Texas, then we could end up high and dry and the chance of a drought becomes higher, like in 1998. Or they could swing up the East Coast like they did in 2016, leaving most of Georgia in the area of dry sinking air away from the center of the tropical systems. There is no way to predict exactly where they will go so far ahead.

Let’s start by looking at the transition from El Niño to La Niña. While El Niño is currently still quite strong, it is showing signs of weakening, with a pool of cooler-than-normal water along the equator in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Subsurface ocean temperatures are also showing the loss of the El Niño heat pool, indicating the transition could be quick. The latest ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) forecast, released last week, indicates that it is likely to return to neutral conditions by the April-June period. It is expected to swing to La Niña by the June-August period. The faster the transition occurs, the sooner we are likely to see the swing toward warmer and drier conditions. Fortunately, we have built up a good reservoir of soil moisture due to the El Niño this past winter, so that will help get us through any early dry spells, but may not last long. It is highly likely that La Niña will last through next winter, so we can expect a sunny winter with warmer and drier conditions than usual in 2024-2025.

While there is not a lot of skill in forecasts for summer climate patterns based on the ENSO phase, we do know it has a strong impact on tropical activity. In both neutral and La Niña years, the subtropical jet that overlies the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic is shifted north, allowing tropical waves to grow vertically into tropical storms or hurricanes more frequently than in El Niño years, when the subtropical jet is strong and right over the area where storms are likely to develop. In those years, the jet disrupts the vertical growth of storms and keeps them weak or blows them apart before they organize. If you look at the number of tropical storms that occur in neutral and La Niña seasons, it is much higher than in El Niño years and they also tend to occur farther to the west, including in the Gulf of Mexico. That makes Georgia more of a target than in El Niño years, although as we know, it only takes one storm to do tremendous damage, as we saw with Hurricane Idalia last year.

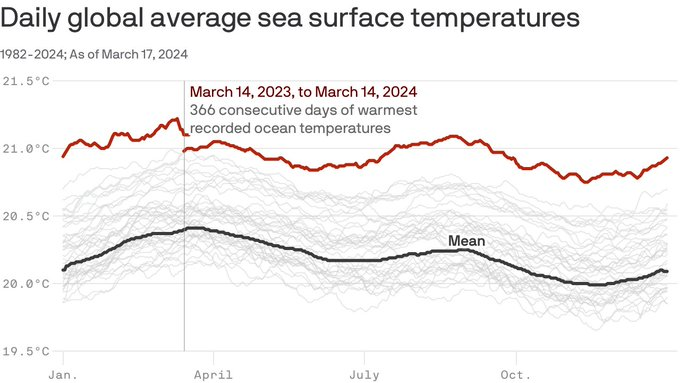

In addition, the sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico as well as the rest of the world are much warmer than normal, and the Atlantic has reported record-setting high temperatures every day in over a year. They are continuing to increase, which is a puzzle that climatologists have not figured out yet. That warm ocean contributed to the above-average number of storms in 2023 even though it was an El Nino summer, but most of the storms stayed over the ocean and caused limited damage to the US, although both Idalia and Ophelia caused problems for farmers and others in the Southeast. This year there won’t be much resistance from the subtropical jet, and so I expect to see a large number of storms develop. While there have not been any official tropical forecasts issued yet, the consensus is that we could easily see 20 or more named storms in 2024. If some of the weaker storms come over Georgia, we will likely be glad for the rain, especially for those who don’t have access to irrigation, but if any of the storms strengthen rapidly due to the warm water right before landfall, wherever it hits will likely be devastated as those areas were from Michael, Ian, and Idalia.

In addition to the influence of La Niña that we are expecting, we are also in a period of warming temperatures across the Southeast as well as the globe as a whole due to the increase of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuel, deforestation, and draining of wetlands. This alone would make it more likely that the summer will be warmer than normal, since in a period of rising temperatures you are more likely to get above-normal temperatures than below-normal temps just based on statistics, although there is variability from one year to the next. We also know now that reductions in sulfur aerosols from cargo ships at sea as well as from shuttering of coal-burning plants on land have led to a clearer atmosphere that lets more sunlight through, warming the surface even more. Some scientists also believe that the eruption of Hunga Tonga in the Pacific, which blew a huge amount of water vapor high into the atmosphere, may also have contributed to the record-setting Atlantic Ocean temperatures, although this is still a matter of investigation.

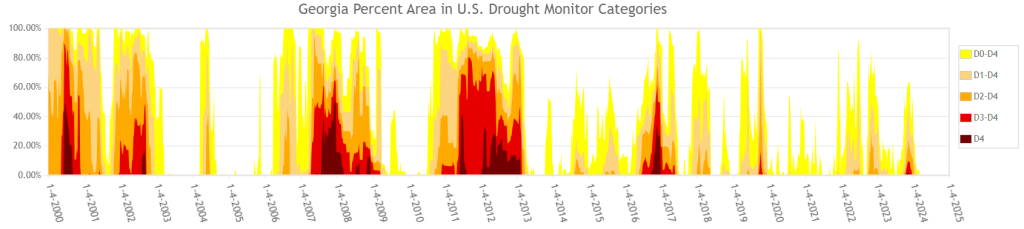

Will we get a drought in 2024? While we are currently quite wet across a lot of the region, the rapid switch to La Niña makes it more likely. Most of our recent droughts in the Southeast started in years when that rapid transition occurred, including 1998, 2006, 2011, and 2016. The warmer-than-normal temperatures and drier-than-normal conditions will contribute to high demand for water by crops as well as increased evaporation from soil and water bodies, and that could cause drought to develop, especially if La Niña develops rapidly. But where, when, and if it occurs will depend on the activity in the tropics and where the storms go, and we won’t know that until they are forming. I would expect to see dry conditions in the fall across the region except where a tropical storm system moves near or over the area.

The new seasonal outlook maps should be posted later this week. I expect they will provide information that is consistent with this outlook. I will post more information in my blog at https://site.extension.uga.edu/climate/ when it is made public.