As we enter December, here is an update on the outlook for winter and spring climate conditions in the Southeast. We are currently in a weak to moderate La Niña, and that is likely to determine the overall climate conditions for the Southeast in the coming months.

According to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, there is a 76% chance that La Niña will continue during the Northern Hemisphere winter (December through February 2022-2023) with a transition to ENSO-neutral favored in February-April 2023 (57% chance). La Niña conditions are associated with warmer and drier conditions in parts of the Southeast during the winter months as the jet stream that controls where precipitation-producing storms is shifted to the north towards the Ohio River Valley. This has the highest likelihood of occurrence in northern Florida and southeastern Georgia, with lower likelihood in other parts of the region.

However, even if the average conditions are warmer and drier than normal, we can still expect to see some outbreaks of cold air push through the region during the winter, so wet spells and even some snow or ice storms are possible, depending on location. Since the La Niña is also weakening, forecasts for what kinds of climate conditions we might experience are also less reliable than if it were a strong event, and that means other climate events like a Sudden Stratospheric Warming, strong North Atlantic Oscillation, or other factors may provide greater influence on the weather and climate this year. There are some hints now that some of these other factors may bring unusually cold air to the eastern US, especially the northern parts of our region, by mid- to late December, but that is far enough in the future that it is not clear exactly how cold it will get or if any precipitation will be associated with that cold outbreak.

The transition to neutral conditions in the spring does mean an increased chance of a late frost. This could be a concern for fruit farmers, who may have received enough chill hours by then (especially if December is cold) that their trees and bushes are ready to bloom when the first extended warm spell occurs. This fall, we started out ahead of normal in chill hour accumulation, but the recent warmer conditions have put us close to last year’s accumulation but behind the long-term average.

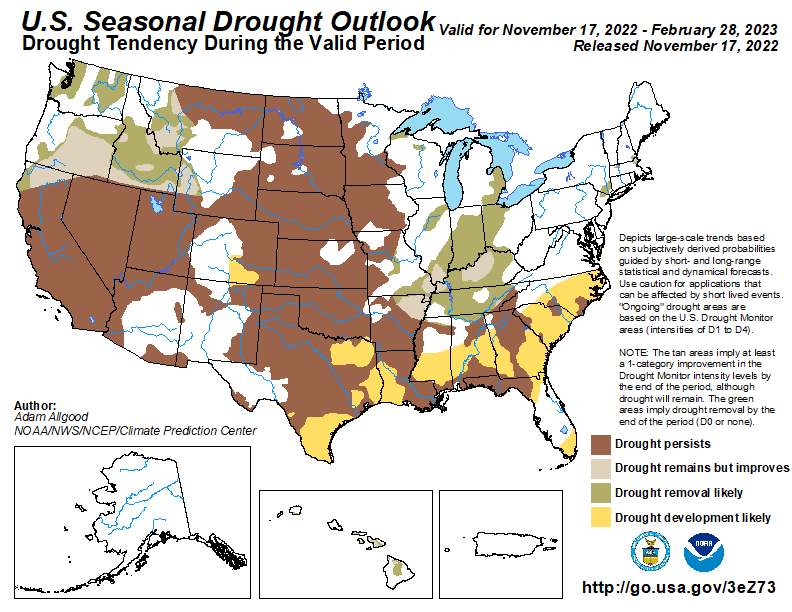

Drought has also been a problem this fall. Most of the Southeast received quite a bit of rain as the cold front passed through the Southeast on November 29 and 30, so I don’t see a big expansion of drought conditions is likely in the near-term future. However, the expected drier than normal conditions from the La Niña could contribute to the drought re-expanding later in the winter, especially in southern Georgia and Alabama and northern Florida. Typically, the growing season after a La Niña is more likely to experience a drought than after an El Niño because of the lack of winter recharge of soil moisture, but that has not been the case for the last two years so it is not a sure thing. We will have a better understanding of what next year’s growing season is likely to experience in late March 2023 when we have gone through the winter recharge period and have a sense of how much soil moisture will be available once the plants come out of dormancy and increase their water use and the temperatures get warm enough to ramp up evaporation.

If we do swing from a La Niña to an El Niño by late summer, that could mean a less active Atlantic hurricane season next year, which could be a relief for farmers. But as we saw this year, it only takes one hitting a vulnerable spot to cause a lot of impacts, so that is no guarantee we will not see damage next year even if El Niño is present.

Updated national outlooks are available from the Climate Prediction Center. You can also use their pages to access the latest ENSO outlook information through the left menu.