Cotton Defoliation Considerations for 2018 (Freeman and Whitaker)

Most of our early planted cotton is quickly approaching (and has approached in some areas) time for defoliation. Cotton defoliation tends to be one of the most important aspects of cotton production each year. Timing and product selection are two of the more critical components regarding defoliation and confusion occurs not only by the thousands of tank mix concoctions but also the differences in personalities of growers with some wanting to pull the trigger too early and some wanting to wait on the very last boll to crack.

Timing of cotton defoliant application can be determined in many ways. However, the methods which we feel are most beneficial involve monitoring boll opening. The cotton plant has bolls of different ages and those bolls will typically open in the order in which they were set on the plant (such that bolls on the bottom of the plant will open before those on the top of the plant). Research in Georgia has clearly shown defoliation application should be made when 60 to 75% of the bolls on the plant are open. Whether one should lean towards 60 or 75% depends upon how uniform the crop is, as a plant that grown under optimum conditions can often be defoliated earlier than one that has gone through periods of stress. In any situation, it is almost always most profitable to defoliate the crop when the crop reaches 75% open boll.

The process of actually determining open boll percentages can be quite time consuming considering that multiple plants in each field should be assessed (and averaged) and this process should be conducted for each field separately. Therefore, there is another method to determine proper defoliation timing which is much quicker and easier. This process involves counting the number of main-stem nodes between the uppermost first position cracked boll and the uppermost first position boll we want to harvest (in some cases there are late set bolls which will not have time to mature that are set in the top of the canopy). With this method in Georgia we consider it is most profitable to defoliate the crop when it reaches 3 to 4 nodes above cracked boll (NACB).

Another method, which can be used in conjunction with determining open boll % and counting NACB is the “sharp knife technique.” This method involves using a knife to cut the bolls in half so that you can see the cross section. A harvestable boll should have lint that strings out as you cut it and the cotton seed should have a darkened seed coat with developed cotelydons. When we say “harvestable” we mean that the boll should be able to be opened with the use of an ethephon product. In some cases, we use this method to determine the uppermost harvestable boll when figuring NACB.

In general, the best way to determine proper defoliation timing is to employ a combination of these methods. A proper timing of defoliation is the first step to a successful harvest. We should point out that most producers could defoliate their crop earlier than they typically do. In Georgia, we have always had to balance peanut digging in with cotton harvest and cotton is typically much more forgiving than peanut when it comes to harvest timing. However, we should make an effort to defoliate the crop when it is ready, as delays in defoliation applications can turn into lost profit. Specifically, delays in defoliation relate into delays in harvest and those delays often turn into lost yield and fiber quality.

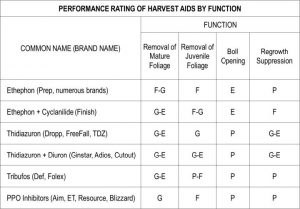

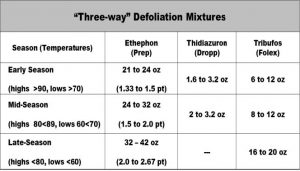

Defoliation of a cotton plant can impact it in four ways. We consider those four functions to be (1) removal of mature leaves, (2) removal of juvenile leaves and plant tissue, (3) preventing regrowth of new leaves after defoliant application and prior to harvest, and (4) opening bolls. A particular cotton crop may need a defoliant application to impact one or more, typically all four, of these functions. Since one product is not effective on all of these functions, tank mixtures of products are applied to enhance the overall effect of the application. Product selection and application rates are determined by the condition of the crop (which functions need to happen) and condition of the environment (temperature, rainfall forecast, soil fertility, etc.). The charts below show defoliant performance by plant function and rates for two of the most widely used and effective defoliant mixtures.

Additional Comments:

- Application water volume and pressure greatly impact overall performance. Often, these two factors are as if not more important than choosing which products and what rates to utilize. One should apply at least 15 GPA when using ground rigs (the more the better, 20 GPA is better than 15 and 25 is better than 20, etc.) and as much water volume as possible with aerial applications. Aerial applications can be extremely effective when products are applied such that spray is blown into the canopy.

- Follow product labels concerning the addition of additives. Additives may aid in uptake of some hormonal defoliants but may also increase the chances of leaf desiccation when combined with others especially with high temperatures. In general, when tribufos (Def) is used in the mixture, additives are not needed to improve efficacy.

- Rainfastness is always a concern with all products however thidiazuron requires a 24 hour rainfree period. However, when thidiazuron is used with other products (especially when mixed with tribufos) the actual rain-free period is reduced. If rainfall occurs before the rain-free period is reached, we suggest that you wait about 7 days and evaluate effectiveness and then make decisions on follow-up applications.

A few comments on cotton defoliation in 2018 with a limited supply of Thidiazuron

Many around the state are concerned about the limited availability of thidiazuron and how that will affect cotton defoliation in 2018. Thidiazuron (TDZ) is a key component of many cotton defoliation tank mix and is excellent at preventing regrowth after defoliation. Below are our thoughts and suggestions on the issue.

- First, go ahead and make plans with regards TDZ for this growing season. In general we vary rates of TDZ based on weather, potential for regrowth and amount of juvenile tissue present at defoliation. If one were to use the three-way on their entire crop, they could budget around 2.5 to 3.0 oz of TDZ per acre of cotton and vary rates in particular situations. With a significant portion of the state’s crop being planted after June 1, a lot of our cotton will be defoliated when conditions are cool enough where regrowth will be less of an issue.

- Logistics – Be timely when defoliating and harvesting. Try to defoliate only what you will be able to harvest quickly and try not to leave cotton in the field for extended periods of time which will allow for regrowth to occur. Without TDZ, regrowth will certainly be much more of an issue in some cases and harvesting quicker after defoliation can limit the impact of regrowth and cotton quality.

- Use proper rate for conditions – since TDZ does not cause leaf desiccation, producers can use higher rates in some places compared to others and get more out of the TDZ we have. Typically, we would suggest using more early during the defoliation season and where more green tissue is present (3 to 4 oz/A on the high end and 1.5 to 2.5 on the low end). When temperatures drop into the lower 60’s at night for several consecutive days the overall effectiveness of TDZ is limited and we could drop it out of the three-way mix.

- Calibrating equipment and use proper GPAs – Make sure your equipment calibration is correct. You may be applying more product than you think. Be sure to use as much water and pressure as possible to get more out of the TDZ that you apply. Defoliants are typically not mobile in the plant and to prevent regrowth TDZ should actually hit the part of the plant where regrowth occurs.

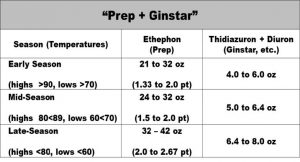

- The three-way is our typical standard for cotton defoliation in Georgia. If TDZ becomes unavailable, the next most effective option is usually ethephon and “Ginstar” (a pre-mix of thidiazuron + diuron). This application can be an extremely comparable option in most situations.

- Lower rates for lower regrowth potential – If all else fails and you cannot get the full rates of needed product, you should evaluate individual fields for their potential for regrowth. There are many factors that contribute to juvenile regrowth after defoliation but fields that are at the highest risk would be high fertility fields that experienced a premature cutout due to drought stress followed by good soil moisture and warm weather at the time of defoliation and after. These crops still have some “horsepower” left and will likely need a full rate. Fields that are at the lowest risk for regrowth are fields that have a heavy boll load, used all of its available nitrogen, and have begun naturally senescing leaves. These are fields that may only require a reduced rate of TDZ.

- So, in general our suggestions are:

- Use the TDZ you have wisely, if regrowth potential is low then consider rates between 1.5 to 2.0 oz/A, if regrowth is expected and there is a lot of juvenile tissue is present consider higher rates between 3.0 to 4.0 oz/A

- If no TDZ is available, mixtures of ethephon + Ginstar (TDZ + diuron) can be very effective at removing juvenile tissue and preventing regrowth. An 8 oz/A rate of the Ginstar products has 2.0 oz of TDZ (a 4 lb ai/A TDZ product) and 1.0 oz of diuron (4 lb ai/A diuron product)

- If TDZ isn’t available and Ginstar products are not used, be aware that regrowth can be more troublesome and harvest as timely as possible.

- If no TDZ is available and regrowth potential is lower, then the mixture of ethephon + tribufos (Folex) can be very effective.

- Mixtures of ethephon + PPO herbicides (ET, Aim, Display, etc.) can also be effective. However, these mixtures are sometimes less consistent than mixtures of ethephon + tribufos (Folex) and in general are more consistent later in the defoliation window.

Finalizing Irrigation Schedules for Cotton (Wes Porter)

Please remember when you are following the Checkbook method represented in Table 1 it was developed based upon average ET values and are not truly representative of individual years. Any Checkbook method should be used as guide and with caution. You should track irrigation and rainfall to determine the crop requirements and make a decision on the amount of irrigation to apply based on irrigation efficiency and current weather conditions. This means that hotter and drier weather would require higher amounts of irrigation, and cooler and cloudier weather would require less irrigation. It is recommended that a rain gauge be used with these curves for accurate estimation of rainfall amounts. In addition more advanced methods such as the SmartIrrigation Cotton App, IrrigatorPro, or sensors could be implemented to develop a more sound irrigation scheduling method. For more information on irrigation scheduling contact your county agent.

As we approach the end of the season, we need to proceed with an educated caution as to when to stop irrigating our crops, especially cotton. Due to our typical high humidity and high rainfall amounts during the fall we typically have problems with boll rot and hard lock. It is important to remember that as we approach open boll our water requirement drops dramatically (Table 1).

It is important to check the soil moisture in your field and determine if you have enough to get you through until defoliation. Keep in mind that most of our soils have a water holding capacity of about 1.0 in/ft. This means that the plant will have access to 1.0” of water per foot of rooting depth. However, this year since it was so we early many of the plants did not develop a very thorough root structure. In most cases we can safely say that cotton is able to access moisture from about a two foot rooting depth. However, this year that may not be the case. This means that the crop may not have access to deep moisture, so it may dry out faster than normal. Once the crop reaches open boll it only requires about 0.5 inches of water per week. As can be seen in Table 1 below, the water requirement dramatically drops after this level. This means that if you can detect sub-surface moisture with a shovel or probe there is probably adequate moisture to last until defoliation. Thus, you should terminate irrigation. Especially if you see any open bolls in the field, irrigation should be terminated.

If you feel like you do not have enough soil moisture to last until defoliation, and there is no guaranteed rainfall in the near future then you may consider one more irrigation application. The recent lower humidity and drier conditions can help reduce the instance of boll rot and hard lock, but do not irrigate too much. Use the table above if you have any questions about finalizing your irrigation for the season. Contact your local county extension agent if you have any further questions.

Terminating Insecticide Applications (Phillip Roberts)

The decision to terminate insect controls can be challenging in some fields but a few basic considerations will assist in that decision. When evaluating a field a grower must first identify the last boll population which will significantly contribute to yield (bolls which you plan to harvest). In some situations the last population of bolls which you will harvest is easy to see (i.e. cotton which is loaded and cutout). In others, such as late planted cotton, the last population of bolls you will harvest will be determined by weather factors (the last bloom you expect to open and harvest based on heat unit accumulation). Once the last boll population is determined the boll development or approximate boll age should be estimated. Depending on the insect pest, bolls are relatively safe from attack at varying stages of boll development.

The table below list approximate boll age in days which bolls should be protected for selected insect pests. Cooler temperatures will slow plant development and subsequent boll age values may increase in such environments. It is assumed that the field is relatively insect pest free when the decision to terminate insecticide applications for a pest is made.

Late Season Management Considerations for Diseases and Nematodes (Bob Kemerait)

Though not over yet, it will not be too much longer until pickers are in the field and modules and round-bales fill the gin yards. Diseases and nematodes have been much more of a problem in 2018 than in any other year that I can remember. This was and continues to be, in large part, due to the frequent rain events and wet weather throughout much of the season. Spread of fungal and bacterial diseases are favored by such.

There are seven significant disease/nematode conditions present in Georgia’s cotton fields now and while there is not much growers can do or need to do about it now, still they should pay attention so as to make the best management decisions in 2019.

- Stemphylium leaf spot is present in many fields and is identified as small-to-moderate sized lesions, often encircled by a dark, purple ring, on leaves showing signs of nutrient (potassium) deficiency. Stemphylium only occurs in conjunction with a potassium deficiency in the plant and can lead to rapid defoliation and significant yield loss. Stemphylium leaf spot is a very important problem in the state and is likely overlooked as growers have either become too familiar with it or do not think that there is much that can be done. Stemphylium leaf spot typically occurs in the same areas of a field year after year- sandier areas, sometimes infected with nematodes. Grower should take special steps to manage soil fertility (and nematodes) to reduce losses to this disease.

- Target spot has been especially widespread this season because of extended periods of wet weather. As I have often said, use of fungicides is not always profitable if the level of target spot is low because of hot and dry conditions. However, I believe most growers who protected their cotton crop with fungicides in 2018 will see some benefit in doing do. We should have some interesting data to share with the growers during the winter meeting season.

- Areolate mildew has been problematic again for the second year in a row across a large section of the cotton production region of Georgia. I am not really sure why that is, but suspect that the fungus successfully survived in crop debris from last year and was brought on again by the rainy season. I am hoping that this disease does not become an every-year occurrence and problem for our cotton producers. We should have some data to share on control and yield after use of fungicides in the upcoming winter meeting season.

- Bacterial blight became established in some fields very early in the season and I had expected it to be a major problem. Statewide, bacterial blight has been a very minor issue in 2018, demonstrating that the development and spread of a disease can be difficult to predict. Growers are reminded to be careful in their selection of varieties for 2019 as resistant varieties are THE most important measure for managing this disease.

- Fungal boll rots are likely to be quite severe in the 2018 season, especially in fields with excessive, rank growth. In some situations, limited defoliation from leaf diseases could actually be a good thing by opening up the canopy and allowing airflow to reduce humidity and dry the bolls. Fungicides are not an effective management tool for control of boll rot.

- Fusarium wilt is becoming an increasing problem in Georgia’s cotton fields. I don’t know if this is because the problem is spreading or simply because growers are paying greater attention to it. Nonetheless, at this point Fusarium wilt can ONLY be managed in our fields by managing the parasitic nematodes associated with it, often by treating the field with a nematicide. Again, we should have some excellent data to share after this field season.

- Nematodes in general (root-knot, reniform, sting and lance) are a significant problem in our cotton fields. Growers are encouraged to take the time after harvest and before cold weather hits to take soil samples from areas of poor growth in order to determine if nematodes are indeed a problem.

Taking stock of disease and nematode issues at the end of the 2018 season should help growers to make effective management decisions for 2019.

Gin Talk (Kane Stains)

As summer winds down, the advent of fall, Dawgs football, and harvest-time rapidly approaches. In just a few short days or weeks, rural Georgia roads will be inundated with cotton pickers, module trucks, and various other harvest-related machinery. Before we know it, all of the blood, sweat, and tears that were poured into this year’s cotton crop will culminate in a string of 500 lb. bales. Throughout the growing season, farmers and managers have labored over their crop, weighing every management decision against the ultimate bottom line. After all, farming and especially cotton farming is the ultimate game of dollars and cents; some would argue that it’s more cents than dollars. One of the final management decisions that one can make is to ensure that once the cotton is defoliated and ready for harvest, it arrives at the gin free of any contamination.

As most are aware, global cotton buyers frown upon receiving contaminated cotton; as they should. Most often, one’s mind immediately gravitates to plastic products when discussing cotton contamination. Of the leading contaminants plastic certainly shows up most often, but cotton contamination is technically any substance in the bale other than ginned cotton lint. Items such as oil, grease, red shop rags, wrenches, chains, cotton string or rope, or the occasional extension ladder have all found their way into harvested seed cotton and some even making it as far as the bale press. Most frequently, yellow module wrap and black horticultural plastic take the “wrap” (no pun intended) for cotton contamination. However, the occurrence of plastic shopping bags found in post-harvest seed cotton is most certainly on the rise.

The problem with plastic contamination is exponentially magnified once the contaminated cotton enters the gin plant. As the seed cotton flows through the system, plastic and other contaminants may become lodged in various nooks and crannies of the machines. Once the contamination reaches the gin stand, thousands of sharp saw teeth grind it into miniscule pieces, thus rendering it nearly impossible to remove at the gin level. This scenario usually creates a two-fold problem because the plastic can remain lodged until a later time, during which another grower’s (potentially contamination-free) cotton is being ginned and thus becomes contaminated. With the use of Bale ID Tags, contaminated cotton can be traced back to the individual farm that produced it. Unfortunately, someone could potentially pay the price for another’s negligence. As a side note, your local cotton gins are doing everything in their power to detect and remove contamination as soon as the module arrives on their yard but they need the help of growers, managers, consultants, and farm staff to ensure that the problem is minimized.

The moral of the story is that Georgia has developed a reputation for producing, ginning, and shipping extremely high levels of superior quality and contamination-free cotton. As you’re riding the farm roads and scouting your crops, or as you’re spending those countless hours aboard a cotton picker, I encourage you to take the time to stop and remove any items that may have found themselves in a cotton field. Whether it’s yours or your neighbor’s, taking the time to remove that “dollar-store” bag from the turn rows will pay dividends in the long run for us as an industry. If Smoky Bear were to advocate for cotton, he’d say “Only You Can Prevent Cotton Contamination.” Safe harvest to all!