Tall Fescue (Lolium arundinaceum), a cool season perennial grass, is an important forage base for beef cattle in north Georgia. Though majority of the total yearly production of fescue occurs in spring, this grass is also productive during early summer, fall, and late winter as well as in mid-summer if moisture conditions are favorable. In traditional tall fescue varieties, the plant contains a toxic fungus. The fungus Neotyphodium coenophialum grows inside the fescue plant (thus called “endophyte”) and is transmitted via seed. The endophyte confers several benefits to fescue pasture sustainability such as drought and stress tolerance, resistance to insects, as well as resistance to fungal diseases, viruses and root-feeding nematodes. The fungus also benefits from this relationship because the plant provides energy and a sustainable environment for the fungus. This beneficial symbiotic relationship between the plant and fungus is considered necessary to ensure optimal plant production and survival.

However, the endophyte produces toxins called ergot-alkaloids. The toxic alkaloids cause “fescue toxicosis”. The toxic effects in livestock that graze infected pastures or consume infected hays cost beef cattle farmers a billion dollars annually in lost revenue each year in the United States. Various adverse effects of fescue toxicosis on animals have been reported, including “summer syndrome”, “fescue foot”, reproductive difficulties, reduced weight gain, decreased milk production, slightly elevated body temperature, impaired heat tolerance, excessive nervousness, and failure to shed winter hair coats in the spring.

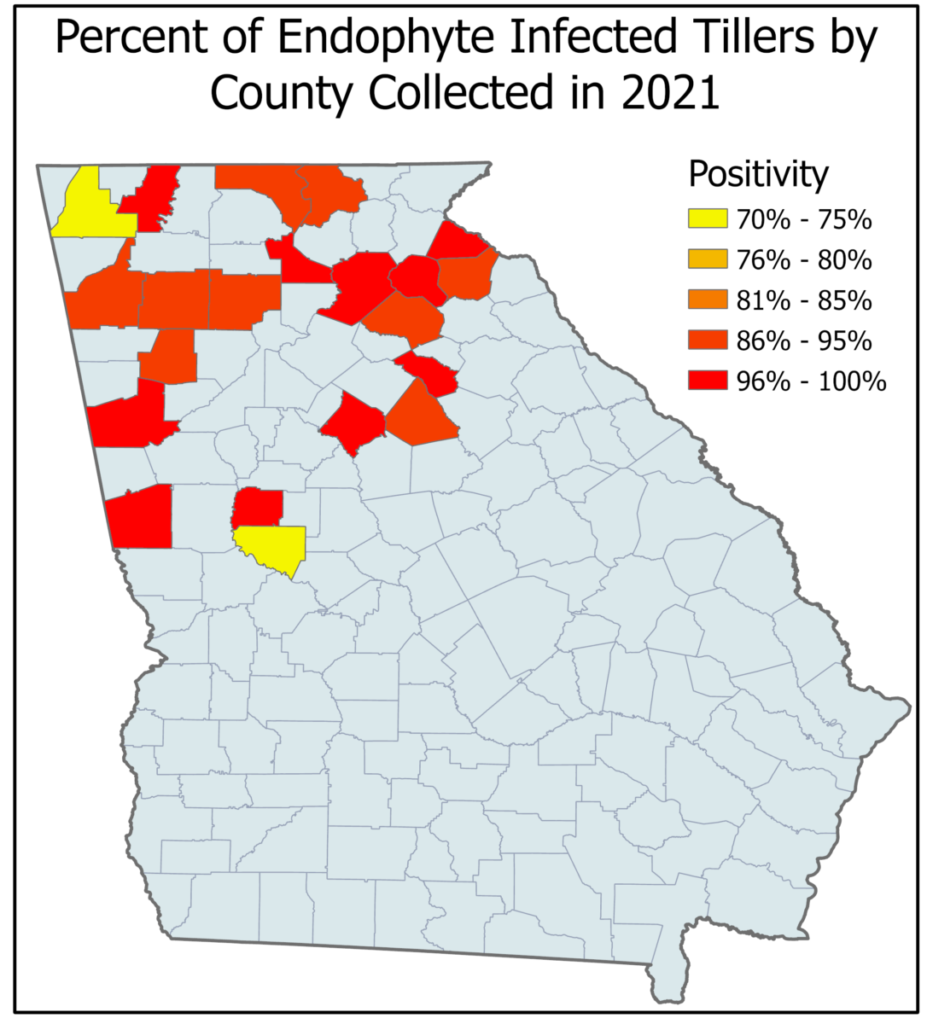

Historically, a vast majority of tall fescue pastures in Georgia and other places in the USA are infected by toxin producing endophyte. Infection levels can be highly variable among the pastures or even within a single fescue pasture. There is a lack of clear and precise information about the nature and extent of endophyte infection in Georgia fescue pastures. Information is needed on the adverse economic consequences of fescue toxicosis in the beef cattle industry to design and implement appropriate strategies to combat this important problem. To address this lack of information, the University of Georgia conducted a survey to assess the severity of toxic endophyte infection in fescue pastures critical to the beef cattle industry in Georgia.

This baseline survey was conducted with grant funding from Georgia Commodity Commission for Beef Cattle to have a preliminary assessment of the extent and severity of toxic endophyte infection in the one million acres of fescue pastures in Georgia. This information should provide valuable insight into existing fescue pasture management decisions, and the extent and urgency of the need for remedial action, such as pasture renovation. The ultimate objective was to develop a “risk profile” for the fescue industry by estimating the percentage of acreage in different risk categories. This would guide educational and remedial programs to target the most needed areas for mitigation.

Samples were collected through collaborative efforts of the grant team and UGA ANR Extension Agents of 21 counties. Emphasis was given to have samples collected as broadly as possible across the fescue belt from approximately Eatonton north. In addition to testing individual pastures for endophyte infection, we also conducted a smaller-scale study of variability of infection within a specific field by taking 4 samples from each of the 2 different fescue pastures at the J. Phil Campbell Sr. Research and Education Center Farm of the University of Georgia, located in Watkinsville, Georgia. For this, each of the 2 pastures were divided into 4 quadrants primarily based on topography and one sample was collected from each quadrant. A total of 56 samples (each containing 30-40 tillers) from 21 Georgia counties were analyzed.

All fescue pastures sampled from 21 counties turned out to be severely infected by endophyte. The lowest infection of 25% was observed in a pasture from Upson county, but the other two pastures from this county had 95 and 100% infection. The mean infection level for the whole study was 94% with a median of 100%. Out of 56 samples tested, 30 had 100% infected tillers. Thus, we found endophyte infection in the fescue pastures in Georgia is widespread and mostly severe.

In addition to testing one sample per submitted pasture, we also tested 4 samples from each of the two pastures at the J. Phil Campbell Sr. Research and Education Center Farm. The results show very minimal intra-pasture variability in endophyte infection with the levels of infection ranging from 90-100% in one pasture (F2) and 95-100% in another (F1).

Figure 1. A map showing the severity of endophyte infection in fescue pastures in various Georgia counties observed through this study.

According to recommendations from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, only in pastures with less than 20-35% endophyte infection can the toxins be diluted by inter-seeding legumes (usually white clover or red clover) or planting other grasses (e.g., bermudagrass, orchardgrass, etc.). However, only one pasture (from Upson county) fell within this range with a 25% endophyte infection and would qualify for applying this recommendation.

According to NRCS, renovation of toxic-endophyte tall fescue pastures with fescue varieties that are infected with a novel-endophyte, that do not produce toxic ergot alkaloids while still providing positive agronomic advantages of a toxin-producing endophyte, is the best option for pastures that have 60% or greater endophyte infection. Thus, all other 49 pastures (except the one from Upson county) of this study, with 70-100% endophyte infection, merit renovation with newer novel-endophyte fescue varieties. This replacement would be a costly investment initially, but would be a cost-effective intervention for the fescue-based livestock systems in the long run.

These baseline survey results will serve as a teaching tool to convince farmers to have their own pastures tested in order to assess the need for remedial management. Since NRCS offers cost-assistance for renovation of fescue pastures with novel endophyte varieties of fescue in some states within the fescue belt, including Georgia, the impact of this survey results are much higher. Furthermore, the outcomes of this survey will help with the current work of the Alliance for Grassland Renewal (https://grasslandrenewal.org).

For full survey results, visit https://aesl.ces.uga.edu/publications/grantreports/.

Thank you to these collaborators: Uttam Saha, Jason Lessl, Daniel Jackson, Abdolmajid Ronaghi, and David Parks, Agricultural and Environmental Services Laboratories, UGA; Lisa Baxter, Department of Crop & Soil Sciences, UGA; Lawton Stewart, Jennifer Tucker, Department of Animal & Dairy Science, UGA; Philip Brown, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Athens, GA

Extension Agents Contributors: Zach McCann, Banks County; Paul Pugliese, Bartow County; Paula Burke/Angie Stober, Carroll County; Josh Fuder/John Bennett, Cherokee County; Clark MacAllister/Jason Hamby, Dawson County; Ashley Hoppers/Jake Williams, Fannin County; Keith Mickler/Kimani Grey-Campbell, Floyd County; Raymond Fitzpatrick, Franklin County; Garrett Hibbs, Hall County; Greg Pittman, Jackson County; Lucy Ray/Tatumn Behrens, Morgan County; Ashley Best, Newton County; Mary Carol Sheffield, Paulding County; Brooklyne Wassel, Pike County; Thad Glenn, Stephens County; Deborah Xavier-Mis, Troup County; Jacob Williams, Union County; Hailey Robinson/Wes Smith, Upson County; Wade Hutcheson, Walker County; and Roger Gates, Whitfield County.