Peanut Insect Update – Mark Abney UGA Extension Peanut Entomologist

The insects (and mites) that really matter in peanut are greatly affected by rainfall. In this year

of pretty consistent rain, lesser cornstalk borer is unlikely to pose a serious threat to the

Georgia peanut crop. If the rainfall continues we will also get a reprieve from two spotted

spider mite. Unfortunately, we are never far away from drought conditions in Georgia, and

spider mite infestations are simmering in some cotton fields right now ready to move to peanut

if conditions become favorable (i.e. hot and dry). Should mites need to be controlled, Portal and

Comite are the two miticides labeled for use in peanut.

On the other side of the coin are rootworms. Rootworms are the larvae of cucumber beetles

(spotted cucumber beetle and banded cucumber beetle), and they thrive in the moist soil

conditions that have been prevalent in most peanut fields so far in 2021. Growers with high risk

fields (those with heavy soil texture and irrigation) are probably scouting or have already made

insecticide applications for rootworms. Due to the abundance of rain, we are almost certain to

see injury in fields that do not have a history of infestation. The only proven management tactic

for rootworm is the application of granular chlorpyrifos. Rootworm injury in untreated plots in

UGA research trials in Plains last week exceeded 60%. That is, more than 60% of all the pods on

the plants had rootworm feeding injury. An infestation of this level is not something we want to

miss or ignore.

August is generally the real start of “caterpillar season” in Georgia peanuts. So far, our most

common mid to late summer foliage feeders, velvetbean caterpillar and soybean looper, have

been relatively scarce, but a few reports have indicated numbers might be starting to pick up.

We also need to be watching for fall armyworm. Correctly identifying caterpillars is important

for selecting the most efficacious and lowest cost insecticide.

Threecornered alfalfa hopper populations always build late in the season, and the insect tends

to like wet conditions, so expect to see a lot of them in the coming weeks. The impact of

threecornered alfalfa hopper feeding on yield is variable, but no one has ever documented

severe yield loss in GA-06G. I think a pyrethroid application can be justified in irrigated fields

where the risk of spider mites is minimal. Even with the abundant rain in 2021, I would not

treat non-irrigated fields with a pyrethroid. There are no other practical insecticide options for

this insect in peanut.

Spray Coverage and Canopy Penetration

By Simer Virk (svirk@uga.edu) and Bob Kemerait (kemerait@uga.edu)

Timely and effective fungicide applications throughout the season are an important tool for

growers to manage and protect yield from diseases like white mold and leaf spot in peanuts.

Considering the recent rains and wet field conditions, peanut growers are likely already behind

and may have missed few applications. Because of this, the importance to make each fungicide

application count – when growers get a chance to get back in the field – is highly critical. Beside

selection of a good fungicide program, attaining optimum coverage for contact fungicides on

and within the canopy is important for effective disease control. Below are few considerations

for improving spray coverage and canopy penetration which can easily be overlooked if a

grower is already behind and sometimes in a rush to get in and out of the field:

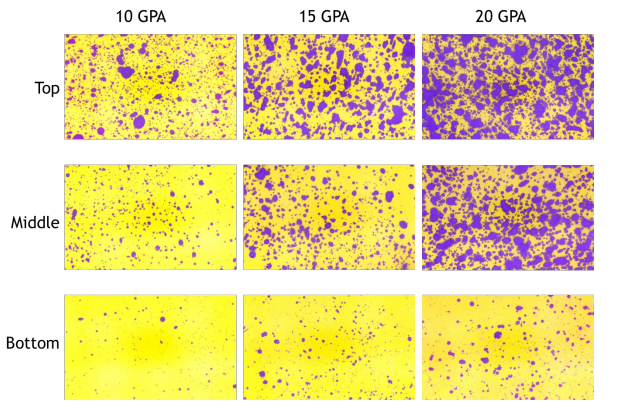

- Spray Volume: One of the most effective ways to improve spray coverage and canopy

penetration is using enough spray volume. The slide below shows spray coverage

obtained at three different positions (top, middle and bottom) in the peanut canopy for

fungicide applied at the rates of 10, 15 and 20 GPA. As observed, the higher spray

volume not only increased the coverage at the top of the canopy but also helped

improve the coverage at the middle and bottom of the canopy due to more volume

penetrating through and into the peanut canopy. While most pesticide labels have a

minimum spray volume requirement (mostly 15 GPA for ground applied fungicides) to

attain adequate coverage, and increased volume can further help improve coverage, it is

critical that growers do not reduce the spray volume below the minimum recommended

volume as it can significantly affect both fungicide coverage and efficacy.

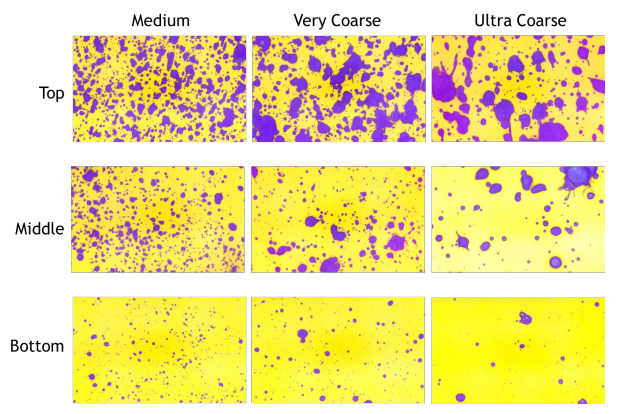

- Droplet Size: Size of spray droplets is also another important consideration for

maximizing the effectiveness of fungicide application as it can influence both coverage

and canopy penetration. The slide below shows spray coverage obtained at three

positions (top, middle and bottom) in the peanut canopy for same fungicide volume (15

GPA) applied at three different droplet sizes. Again, it can be clearly observed that

smaller droplets provided better coverage and canopy penetration while the larger

droplets, especially ultra coarse, were unable to penetrate the peanut canopy resulting

in considerably low coverage at the middle and bottom of the canopy. Since only some

fungicide labels list droplet size requirements, it is suggested that growers utilize a

combination of nozzle type and pressure that produces medium to coarse droplets to

maximize the product efficacy. Growers who prefer to use dicamba nozzles for spraying

peanut fungicides should be extra careful considering the the influence of decreased

coverage as well as reduced canopy penetration with larger droplets.

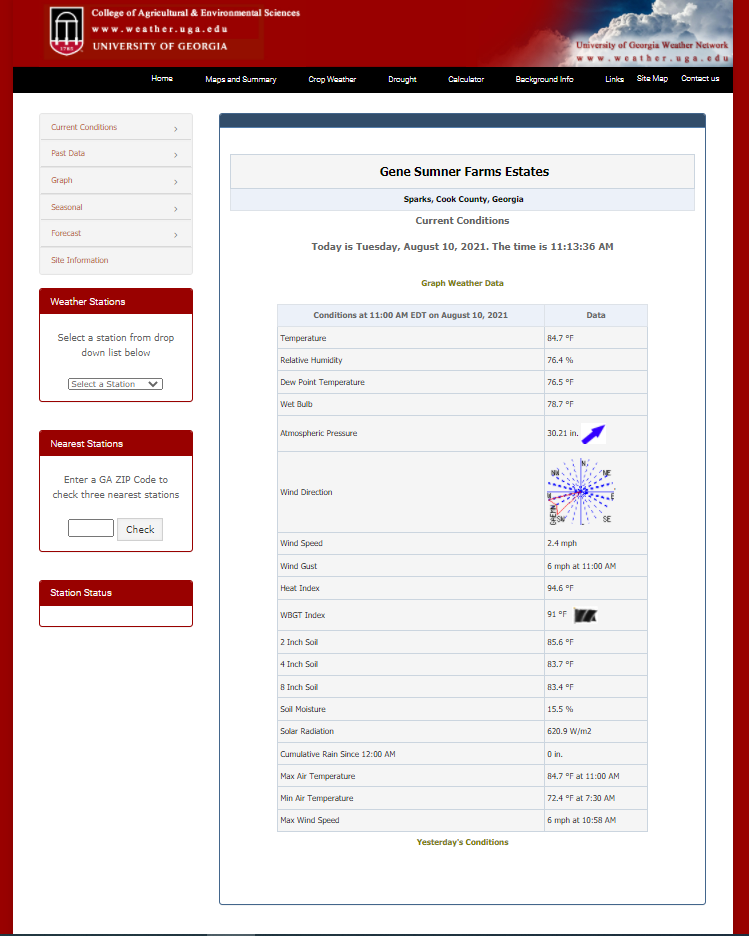

Cook County Weather Station

Cook County now has a “UGA Weather Station” in Sparks installed about a month ago. The station is a tri-pod apparatus about 10′ tall that collects wind speed, soil temps, humidity, dew points among other things. The data collected is extremely accurate. It saves this data so that you can go back to a certain day in time to see how much rain we received for example. This information is available to the public. https://georgiaweather.net/?content=calculator&variable=CC&site=SPARKS

How to Fertilize Drowned Out Cotton (Glen Harris): Obviously, it has been a wet growing season in

South Georgia. It reminds me of 2013 when it rained every day in June. Up until then I really didn’t think

you could drown a South Georgia sand. But when all the pore space in even our sandy soils gets filled with

water we reach saturation or ‘waterlogging”. This may cause the cotton plant to shut down or not function

properly to the point where it doesn’t take nutrients up from the soil very well if at all. Since nitrogen is the

fertilizer nutrient needed in largest amounts by plant, the nitrogen deficiency symptoms or “yellowing” of

the leaves shows through the most.

Some areas of the cotton belt in Georgia have received more rain than others. Also, It appears that early

planted (May) cotton is looking better than late planted (June) cotton. I’ve heard a lot of people say “ I

leached out or lost all my fertilizer”. I’ve also heard growers say it’s been so wet I have not been able to

sidedress my cotton”. “Should I replace some N and K on the ground? Should I switch to foliar? What

should I do?

Normally we (UGA) would recommend applying ¼ to 1/3 of your total N rate and all of your K to the soil

at planting, followed by sidedressing N between first square and first bloom. Normally…we (UGA) would

recommend switching over to foliar feeding N and K after the 3rd week of bloom, or in other words no more

N or K soil applied after this point. But this is not a normal year (is there such a thing anymore?).

So let’s look at a few common scenarios: 1) May planted cotton and you were able to get your sidedress

nitrogen applied. Cotton has been blooming for at least 3 weeks, now you’ve had a bunch of rain and the

crop looks yellow. Should you apply more N and K to the soil (if it gets dry enough to get a fertilizer truck

or buggy in the field)? Probably not. For three reasons. One, the N and K may not be all leached out. Only

the nitrate form of N is leachable and K is not as mobile as N. Two, the waterlogging is hopefully temporary

and as soon as the soil dries out some the plant can take up N and K again. And three, since the cotton has

been blooming for at least three weeks, the roots are not as efficient at taking up nutrients, plus they may

have been damaged or compromised by the wet weather (and maybe some nematodes too). Basically, even

if you apply more N and K to the soil the plant will have a difficult time taking them up. So the

recommendation is? Foliar feed with N and K.

Scenario number 2: June planted cotton just starting to bloom and has not been sidressed with N. Looks N

and K deficient. Since the cotton has just started blooming there is still time to soil apply N. The

recommendation would be to apply 30-50 lb N/a to the soil. I would not soil apply K at this late point. And

even after soil applying N, be prepared to foliar feed with N and K after the third week of bloom.

Scenario 3: June planted cotton that has been blooming for 3 weeks and no sidedress N applied. This is a

tricky one. Again, normally we would switch to foliar feeding at this point. However, it would be difficult

to apply enough nitrogen foliar. Therefore, I would still apply 30-50 lb N/a to soil on this cotton. As in

scenario number 2, time is an issue, with only 4-6 weeks of potential boll setting time left you don’t want

to go with too high of rate in either of these situations.

So a few things to keep in mind:

1) Not all of your soil applied N and K may have leached out.

2) Swithc to foliar N and K after 3rd week of bloom (unless no sidedress N has been applied)

3) Petiole and tissue sampling are a good way to confirm if you are N or K deficient.

Stinkbug Management (Phillip Roberts): Southern green and brown stink bugs are the two most common

stink bugs infesting Georgia cotton. Both have sucking mouthparts and damage cotton by feeding on the

seeds of developing cotton bolls. In addition to mechanical damage, feeding allows for the introduction of

boll rot pathogens. Internal symptoms of feeding on medium sized bolls are the most reliable indicator of

stink bug infestations. Internal damage is defined as warts or callous growths on the inner surface of the

boll wall and/or stained lint. This wart or callous growth is easily visible less than 48 hours after the stink

bug fed on the boll. As bolls mature and open, damage often appears as matted or tight locks with localized

discoloration that will not fluff. Severely damaged bolls may not open at all. Research also suggests that

in addition to yield loss, excessive stink bug damage can reduce fiber quality.

Scouting for stink bugs should be a priority as plants begin to set bolls. In addition to being observant for

stink bugs, scouts should assess stink bug damage by quantifying the percentage of bolls with internal

damage. Bolls approximately the diameter of a quarter should be examined. Bolls of this age are preferred

feeding sites for stink bugs can be easily squashed between your thumb and forefinger. It is important that

bolls of this size (soft) are selected. The number of bolls per plant which are susceptible to stink bugs is not

constant and varies during the year. The greatest number of susceptible bolls per plant generally occurs

during weeks 3-5 of bloom. During early bloom there are relatively few bolls present. During late bloom,

many bolls are present but only a limited number may be susceptible to stink bug damage (individual bolls

are susceptible to stink bugs in terms of yield loss until approximately 25 days of age). A dynamic threshold

which varies by the number of stink bug susceptible bolls present is recommended for determining when

insecticide applications should be applied for boll feeding bugs. The boll injury threshold for stink bugs

should be adjusted up or down based on the number of susceptible bolls present. Use a 10-15% boll injury threshold during weeks 3-5 of bloom (numerous susceptible bolls present), 20% during weeks 2 and 6, and

30%(+) during weeks 7(+) of bloom (fewer susceptible bolls present). Environmental factors such as

drought and/or other plant stresses may cause susceptible boll distribution to vary when normal crop growth

and development is impacted; thresholds should be adjusted accordingly. Detection of 1 stink bug per 6

feet of row would also justify treatment.

When selecting insecticides for stink bug control it is important to consider other pest such as whiteflies,

corn earworm, aphids, or mites which may be present in the field. The objective is to control stink bugs but

also to minimize the risk of flaring other pest which are present. A couple of bullet points below to consider

when selecting a stink bug insecticide:

• Consider week of bloom and use the dynamic threshold.

• Determine ratio of southern green to brown stink bugs, organophosphates provide better control of

brown stink bugs compared with southern green.

• If whiteflies are present, use bifenthrin and avoid dicrotophos during weeks 2-5 of bloom.

• If corn earworm is present consider using a pyrethroid if brown stink bugs are low or using a

pyrethroid tank mixed with a low rate of an organophosphate if brown stink bugs are most

common.

• If aphids are present, include dicrotophos and avoid acephate if an organophosphate is needed. If

mites are present, avoid acephate if an organophosphate is needed.